Treating Malnutrition with Compassion

Carrie Flaherty is a volunteer nurse serving at St. Therese Hospital in Nzara, South Sudan. Here she shares the story of Rodia and Ajok – a mother and child who arrived at the hospital in desperate need of medical care and compassion.

I first met baby Ajok on New Years Eve at St. Therese Hospital in Nzara, South Sudan. As I walked through the waiting area, she caught my attention because of her weak, high pitched cry and the feeble way she clung to her mother. Even more concerning was the obvious severe acute malnutrition (SAM) that she was suffering from.

She was literally skin and bone, every rib could be counted. Her feet were swollen and her hair was brittle, sparse, and orange-tinted due to vitamin deficiency. At 15 months of age, Ajok was only 15.2 pounds (6.9 kg). To put that into perspective, a typically developing child should be between 21-24 pounds .

She also had a high fever, malaria, anemia, and an upper respiratory tract infection. Young children with lowered immune response, no energy reserves, and acute malnutrition face disproportionately high mortality rates.

“Around 45 percent of deaths among children under 5 years of age are linked to malnutrition.” -WHO

Upon arriving, Ajok was immediately given anti-malarials, antibiotics, and we started her on a F-75 formula for malnutrition (F-75 is the starter formula for malnutrition treatment). Ajok’s treatment plan requires a strict regimen of feeding, with only this special formula every three hours, day and night. The volume is adjusted based on weight. When it was clear she was handling the formula, Ajok progressed to the F-100 formula (F-100 is the volume used to treat severe cases of malnutrition), still at at rate of every three hours. Unfortunately, after a few days Ajok started losing weight instead of gaining.

In caring for Ajok every day, I couldn’t help but notice how dejected and detached her mother, Rodia, was. Rodia spoke very little, nearly always looked at the ground, and seemed unable to consistently feed Ajok the prescribed formula. I realized, that in order to help this little one, we first had to help her mother.

With the assistance of a translator, I learned that Rodia was abandoned by her own mother at a young age. Her husband is a soldier and they live in the barracks. During the two weeks Rodia and Ajok spent at the hospital, he never visited.

I also learned that Rodia’s first two children died. Now, Ajok was severely malnourished, and she was pregnant with her fourth baby. It was clear that no one had ever shown Rodia how to be a mother, let alone tell her that she is loved, important, and has dignity.

In that moment, there were so many things I wanted to say that could not be adequately translated. Counseling and mental health services are non-existent in this fledgling country. Depression, PTSD, and anxiety are common but go unaddressed.

It is difficult to find the words to console a mother who has lost two children, even in my native language. So, as silly as it sounds, I started with a smile. Every day moving forward, I made an intentional effort to engage this mother, to show her that she matters, and that I am happy she exists. I wanted to help her realize that she is a good mother, capable of caring for her children. I wanted to give her a sense of hope that she could break the cycle of depression, neglect, and death that she had grown up learning to expect.

Sadly, there are few opportunities for women to provide for themselves in rural South Sudan. With no formal education, I know that Rodia’s physical circumstances are unlikely to change. But still, I hope that we were able to instill in her a positive sense of self worth, and a belief in her innate value as a human person, beloved by God.

Gradually, Rodia became more engaged in caring for Ajok, preparing and feeding her the formula more attentively, and even helping to keep the ward clean with the other mothers.

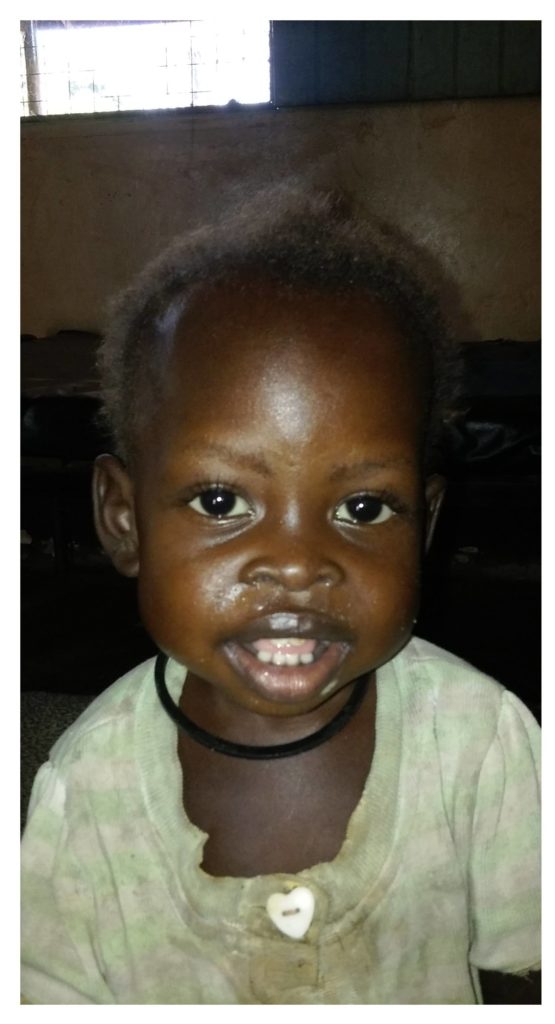

As the week progressed, Ajok finally began to gain back the weight she had lost. Towards the end of the week, I was overjoyed to find her playing with the wooden activity cube, the only toy in our pediatric ward. Even more heartwarming was when she began to smile!

As Ajok regained her strength, it became apparent that she has quite the little personality, with a surprising skill for spitting out medication. But, despite us having to keep a close eye on her after administrating medication, this challenge was welcomed. It meant that she had the energy to be belligerent! Also working in our favor was the fact that Ajok seemed to like the F100 formula and plumpy-nut paste making it easier for her to gain weight.

After two weeks on the unit, Ajok and Rodia were ready to be discharged. Before leaving, Ajok was scheduled to follow up with the outpatient clinic for supplemental feeding and continued support.