Managing Malnutrition in South Sudan: An Interview with Natemo William Louise

It’s estimated that over six million people in South Sudan face food insecurity. It’s a crisis that the United Nations reports is driven by the arrival of COVID-19, in addition to ongoing economic and social challenges.

We recently had the opportunity to speak with Natemo William Louise*, CMMB’s Child Nutrition Program manager in South Sudan. Joining our mission in 2018, William has played a critical role in integrating our initiatives and expanding our impact—even in the midst of COVID-19.

In the interview below, William shares his experience managing the program and outlines the underlying causes of acute malnutrition that go beyond food insecurity.

*Natemo William Louise goes by William.

Give us a sense of the situation in South Sudan. Why does the country continue to face a high prevalence of malnutrition?

We surveyed for food security last October and all five counties we work in are below the global threshold that identifies a nutritional emergency, according to WHO standards. But still, we see children in the communities presenting with signs of moderate to severe malnutrition. That’s because a lot of factors contribute to malnutrition, including feeding practices for example. You might find enough food in the household during a home visit, but children are still presenting signs of malnutrition because their mothers have moved to complimentary feeding too quickly. This of course affects the child directly.

What inspired you to pursue a career in nutrition programming?

Nutrition is an area I’ve been interested in ever since high school. I grew up in a refugee camp in Kenya. My family had left South Sudan when I was just ten during the war. But after high school, I had the joy of returning. As a high school student, I didn’t feel like I had enough knowledge to offer. You just have that thing that inspires you and, for me, it was asking myself how I could help my community.

“You just have that thing that inspires you and, for me, it was asking myself how I could help my community.”

So, I went back to college and started studying nutrition because that was an area that lacks the human resources and manpower. But really, it was the children of South Sudan that inspired me most. Pursing a career in nutrition was one of the ways I could help them.

I’ve been in nutrition programming for nearly five years now and I’ve seen suffering populations, the rising prevalence of malnutrition, and the impact it has on children. It has only inspired me to work harder. I really feel like the knowledge I have should be used where it is needed most.

Tell us about CMMB’s nutrition program. In what ways does it allow you to reach the children you’re inspired to serve?

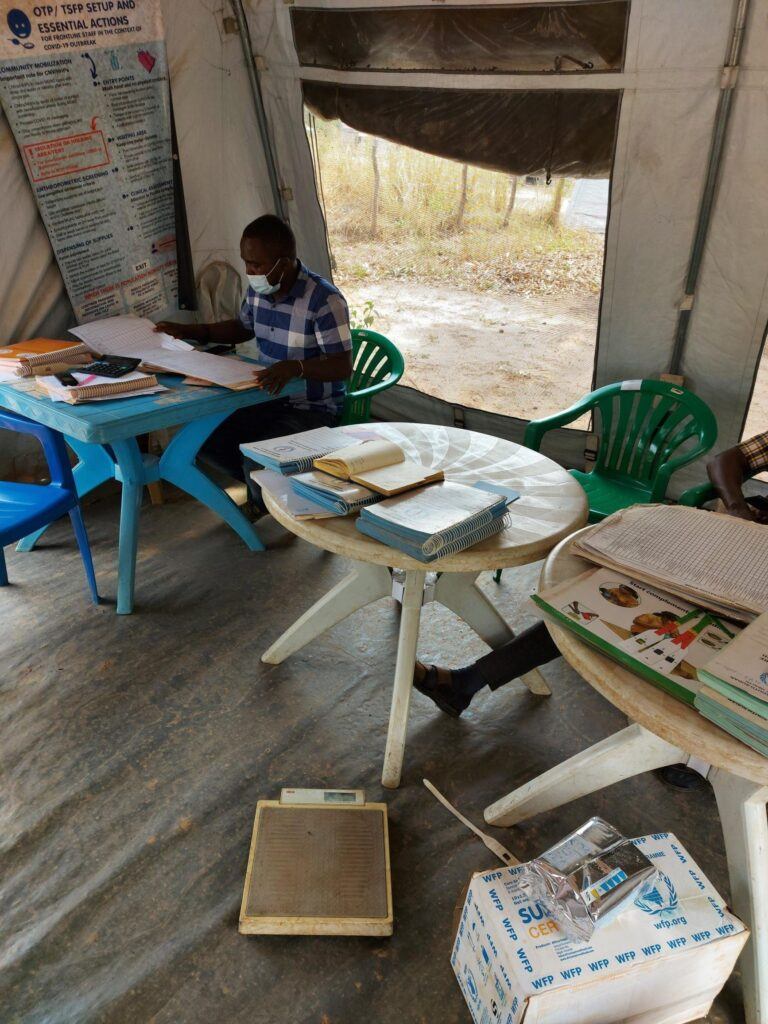

We focus on several areas in community management of acute malnutrition. The first is the outpatient therapeutic program. We call it OTP and it deals with home-based treatment. Children are screened for malnutrition, and if they are not found to be sick, they are provided resources to support their nutrition at home.

Another area of focus is the supplementary feeding program, which deals with children suffering from moderate acute malnutrition. These are children who are at high risk of developing severe malnutrition. We provide these families with home-based treatment.

The other focus area is on children who have been identified as having both severe acute malnutrition and medical complications. For example, the most common childhood illnesses we see are pneumonia and acute diarrhea. If they have severe acute malnutrition and they present with these complications, they receive inpatient care in a local health facility.

In addition to those areas, we also deal with prevention. Prevention work happens in many ways. For example, we can prevent complications like diarrhea through the provision of soap. This in turn, helps promote healthy nutrition practices by encouraging hand washing before feeding.

Another prevention method is of course nutrition counseling. We call it maternal, infant, young child nutrition. This counseling supports and educates mothers on feeding practices, starting with breastfeeding. We talk about things like exclusive breastfeeding and extended breastfeeding.

For context, we encourage exclusive breastfeeding of children from birth to six months. Following the six months we recommend children be introduced to complimentary feeding. The goal of this counseling is to help mothers become more knowledgeable about their child’s nutritional requirements.

You have managed this program through a pandemic. How did you continue to provide communities with these vital resources during such a challenging time?

In the context of COVID-19 we’ve had to adapt our programming models. For example, our community volunteers use the MUAC (mid-upper arm circumference) measurement to screen for malnutrition in children. Placing a measuring tool around the child’s arm, the volunteers can determine whether a child is malnourished, and to what degree. Prior to the pandemic, community volunteers were tasked with this type of screening.

At the onset of COVID-19, this role transitioned from community volunteers to mothers after a series of trainings. This is one of the adjustments that have allowed us to continue our work despite COVID-19.

CMMB has launched several programs in South Sudan. How do all of our initiatives work together to serve communities in need?

We do everything we can to make sure we use existing community structures to reach and refer children.

For example, as a partner organization of UNICEF, CMMB was asked to begin distributing Vitamin A capsules to communities to support nutrition. At first, the campaign was only achieving 60% in terms of reach. So, we decided to integrate our efforts with CMMB’s CHAMPS program, which focuses on providing care for pregnant women and children under five. Because children under five were our primary target for the Vitamin A campaign, we were able to better identify beneficiaries through the child protection program’s catchment.

Having this synergy across programming really provided input and support in the quality of nutrition care.

Jovana Wilson a 2 year old child is assessed for malnutrition, and after she was diagnosed with acute malnutrition. She is at the CMMB clinic in Rimenze IDP settlement, out side of Yambio, South Sudan.

Is there a particular community member, volunteer, or patient whose compels you to continue your work?

I remember once case where a child was brought to the health facility with very severe malaria. She was called Yama. This was early in my career.

In addition to the malaria, Yama was also severely malnourished. You could see her ribs and her sunken eyes.

Based on my assessment, Yama needed to be immediately enrolled in a nutrition program after an extended hospital stay. But Yama’s mother believed she needed to be seen by a traditional healer and removed the child from our care.

Yama later returned to the hospital, but in a much weaker state than the first time we treated her. We tried everything we could, but she eventually passed on.

This was an experience that showed me the regional context. Sometimes you pour your energy into the treatment element only to realize that the underlying community practices also require addressing. And that was the case for Yama.

As difficult as it is, all we can do is try and learn from these outcomes. For instance, I recently saw a similar case. We had another mother come for treatment after seeking help from a traditional healer.

Like Yama, the child was very malnourished and very weak. Through treatment at the facility, we were able to witness the child transition from being severely malnourished to moderately. When assessing the child we saw he was gaining an appetite and becoming more active and eventually we were able to discharge him.

After discharge, the child was still supported through home-based treatments. The mother was so happy to see her child healthy enough to play again.