The Girl with the Pink Skirt: Former Child Soldiers in South Sudan

Listen to the podcast:

“Thank you, Gloria. I’m sorry. I’m sorry for—I don’t know what I’m sorry for—the state of the world perhaps.”

It’s almost five o’clock on a warm spring evening in Yambio, a state capital in the west of South Sudan where I’ve been meeting and interviewing girls recently released by rebels from the jungle, where they’d been taken against their will to work as domestic assistants, informal wives, spies and foragers, and looters.

Every tale has been different, but each one has featured a harrowing list of crimes, both against the girls and against the local population. South Sudan gained independence in 2011 after almost 30 years of conflict against her Northern rulers, the Sudanese, but collapsed into civil war in 2013 as a result of internal politics turned violent.

In the West, when two political figures fall out, we discuss and debate on television. Here it resulted in arms being taken up and girls like Gloria being abducted from villages, from schools, from their families, sometimes with their families.

The recent ceasefire at the end of 2017 has given a measure of hope—cautious and fragile—that the country can start building towards a more stable and prosperous future. As part of this, children and young adults who were co-opted by the rebels into taking up arms or serving those who did, are being formally rehabilitated and reintegrated into their communities.

And that is why I am apologizing to one of the girls, a 17-year-old called Gloria, who has just asked me if there is any chance of our providing a plastic sheet for the simple hut that she is likely to soon call home, the hut having being damaged recently in a storm.

A humble ambition; a sheet to keep the rain off her head before she can even consider the future.

How do you begin to articulate the state of lives here in South Sudan?

One of the girls told me that she had witnessed a soldier having his heart cut out, which was later eaten by the rebels. I heard many times of drugs being used to numb their minds to the consequences and meaning of acts they were forced to perpetrate against local communities.

A feature of the cruelty that occurred in the jungle was the forcing of young people to witness—and at times participate in—barbaric acts to conscript their minds to the lore of violence. It can be very easy to normalize, to numb oneself to the language they use to describe the violence in their lives, to become a little blasé, when the words rape, murder, and torture are used in every interview. But consider what these words mean, consider the impact the acts must have on young, impressionable minds. To see life ended, to feel a part of this horrific act at such a young age.

One of the girls saw her brother forced to murder someone, another described how the rebels would slaughter prisoners without bullets to save ammunition. They talk about beatings for insubordination. One girl suggested her father was killed for objecting to their presence. The girl’s father has not been seen since they arrived in the bush.

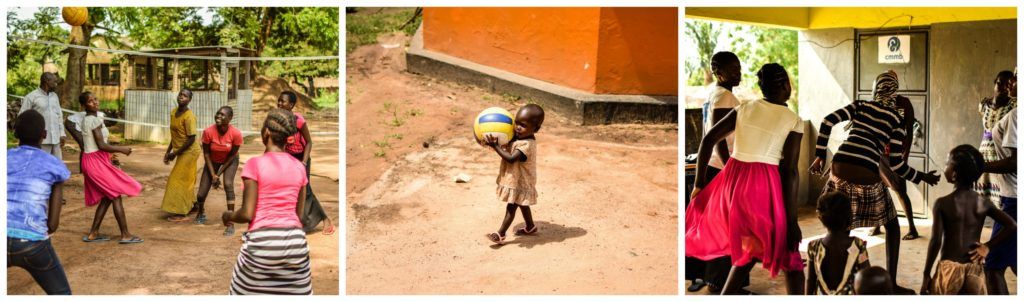

Throughout the day, the staff organize activities—volleyball, dancing, group games, high energy, positive, fun. The girls display a competitiveness, a fieriness, a joy, in such moments, which you can lull you into complacency about their states of mind.

One minute, you watch a girl celebrating a volleyball point or dancing freely with her friends, the next she’s quietly telling you about her life in the bush, nervously fiddling with her hands or a ball of polyester yarn they use to practice sewing. The scene moves between happy youth group and counseling session rapidly. Hope for the future, the memories of the past, all mingled together now in my memory.

And again, the complacency sets in. I have to force myself to imagine the lives they led just months ago in the jungle, while I watch them play or dance. Months ago, by their own accounts, they lived in fear and suffering, unable to express any basic, positive human emotion.

Every time I have asked—gently—if there was anything positive about life with the rebels, wondering if maybe they found redeeming comradeship in hardship, the answer has been swift and brutal.

The moral complexity of their choices, the varying levels of complicity in the acts of war, does not pass me by. Some of the girls became ‘wives’ to soldiers, many of them participated in looting, and most of them will experience suspicion and even hostility when they return home.

Every conflict in history involves forced cooperation, the basic human instinct to survive. How many people have the recklessness to defy a gun or a knife in the face in the darkness of conflicts far from watchful eyes? The moral taint and judgement of collaboration lingers in this traumatized society; neighbors recall crimes committed by children who once ran freely through the fields.

The stain of participation and moral complicity is rarely borne out by the commanders or leaders who sign the agreements and have the means to hide away, but by the ordinary girls who were forced on threat of life to steal crops, to act as spies, and watch as prisoners were murdered before their eyes.

One of the striking features about the girls is their impatient desire to return to education. I am accosted by several of them in the brief time I am with them in the rehabilitation center, a none so subtle demand for help with school registration and fees.

Early on, I notice one girl in particular who is forward and friendly, asking about life in America (I am from the UK) and when my charity’s American head would visit again. I naturally assumed a degree of affection from her towards both him and vicariously myself, as if she were a simple 15-year-old batting her eyelids at exciting foreigners.

But quickly I realized my mistake. This girl is not motivated by curiosity of the West, not the glamour of white people. She has a practical, direct agenda: she wants to escape this land. This is no childlike innocence, but rather hard nosed reality, a plea for life to give her a break.

When the fifth girl has approached me for support, I find my uttering of cliches and empty truisms demoralizing to my own ears. Telling them it’s difficult for me to fund a term’s education for $50 is a lie, albeit a lie borne of a desperately difficult consideration: where does one draw the line? To fund one can be to fund all; to fund one term, can be to fund for life.

Charity, I am told repeatedly, must be sustainable; it must be about the long term, and not a simple handout. But charity can also surely be the short-term too, and if we start by excluding anything that is not demonstrably long term, surely we consign the most desperate and vulnerable to a fate resembling a slow death.

The girls are soon to move out of the rehabilitation center. I spoke to 10 girls and not a single one had the hope of returning to a house with a responsible, male figure who could protect them. Because no matter what our perception of gender is in the West, in a patriarchal society like South Sudan, what matters most for teenagers is the presence of support from a father—to fund education and to protect them from malevolent influences. One of the girls told me that if she is not accepted back by an elder sister, she will live with anyone, anywhere, in the community. I feel sickened by the implication in her words. Anyone.

But even when a girl has a clear idea of where to return, there is little hope of formal education for some of them, little spare cash, and most of them talk of vocational training. How swiftly my mind imagines a vocational course in a college, the hands-on training schemes in the West that we sometimes disdain. But here vocational training could mean working for nothing in the community, at the mercy of forces beyond my imagination. Perhaps this works out; perhaps they will become seamstresses and tailors; yet somehow this feels uncertain.

To my surprise, two of the girls say they wish to become doctors. When someone says this in my country, I caution them to do some work experience, get an idea what level of commitment it requires, perhaps offer help with an application form. Here, how can you even begin to plot a route from the jungle to the only medical school in the country, far away in the capital? I may as well draw them a map to the moon, it feels.

The girls have formed a tight knit circle, the atmosphere of sisterhood abounding. They wash each other’s clothes, do each other’s hair, dance together, occasionally fall out. I notice how comfortably and naturally they look after each other’s children, the 10 or so children belonging to a group of 32 girls under the age of 18. I feel very male here, not unwelcome, but here according to their rules, on their terms, and a little awed, a little intimidated by the atmosphere. I think and I hope that right now, these girls would defend each other with their lives.

But when they leave this ‘safe space’—an overused expression from home, more likely to refer to intellectual freedom than physical freedom—they will re-enter a male world that will not see them as children needing space and time to mature into the adult world. This world will demand much of them, offer little, and exploit any weakness without hesitation. The world they return to will contain fewer games of volleyball and more hard labor.

I ask a few of the grils what their hopes are. I ask what the challenges were, living in the jungle. It feels like I’m interviewing them for a job and I silently chastise myself. One of the hardest parts of the interviews is finding a shared language; I suspect my translator and guide is adept at turning my naive questions into something the girls can relate to.

South Sudan has hope; the hope of youth. Can it build and nurture a generation of young people who feel invested in peace and prosperity? Can it find a way to create amicable debate and problem solving beyond the gun?

My immediate challenge is to find a way to articulate the experience of young people who lost years of their life to conflict and violence, without resorting to banal apologies and stereotypes.

I ask one of the girls how she ended up in the bush. She answered for six minutes. My translator could only remember about one minute of what she said. I recorded it though. Now, I owe it to her to get her full answer translated. But what comes out of that interview, all these interviews—what emerges from the jungle in the hearts, minds, and mouths of these young people—will define this country for long after I have left.

Several of the girls asked how they could leave the country to find opportunity. If we could take 32 girls, who have known injustice and suffering beyond a lifetime for us out of this country and give them a fresh start, if we had the resources to do it, would we?

For now, they are stuck here, and all we can do is hope that somehow they will get the support they need to develop into the adults of tomorrow who will believe in peace and reconciliation.

I sleep fitfully. A mosquito has penetrated my net and my mind. It now lurks like a troubling thought. I wake up and search for it. Eventually I find the mosquito and kill it, but the thought is not so easily dealt with.

How can I arrive in these girls’ lives with an expensive camera, a mission to accomplish, and then leave?

I realize something. For these two months, there is something very special going on in their lives. For maybe the first time, they have been given space, time, and permission to express themselves as young adults. They have tested weary heads, formed friendships, known fun and freedom, and been shown a world without fear and violence.

Yet, when they leave, we may not be able to guarantee anything more than a plastic sheet over their heads.

Can we risk returning them to a world of cruelty and violence? Can we really save them from the abyss and then toss them back in again?

Gloria is talking further about where she will live when she leaves the center. She left the jungle with nothing, but received some clothes when she arrived at the rehabilitation center, including the pink dress she is wearing now. She wonders what will happen to her possessions when she leaves, the fragile life she’s rebuilding.

It’s this thought that makes me upset. She looks lovely in the pink dress, like any 16-year-old around the world, growing into adulthood, finding her way, expressing herself. Two months ago, she wore rags and lived in fear for her life. Now she’s wearing a pink dress. But what about tomorrow?

How can I leave them?

I want to cry. The luxury of emotion and imagination.

Contributor: Dr. Matthew Jones is a UK-trained doctor currently serving at the St. Theresa Hospital in Nzara, South Sudan. In addition to his clinical and teaching duties, Dr. Jones is sharing his observations and learnings about South Sudan, the staff and beneficiaries of CMMB, and our programs on the ground.