“Be Ready to Learn” — An Interview with Volunteer Nurse Stephanie Onoh

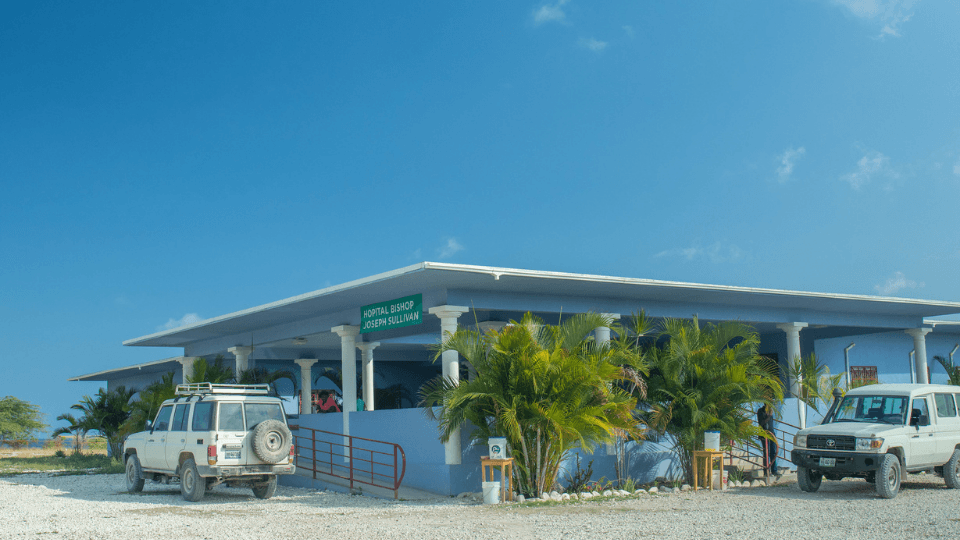

Back in January, Stephanie Onoh traveled to Côtes-de-Fer, Haiti to serve as a nurse at the Bishop Joseph M. Sullivan hospital. Volunteering alongside her mom for five weeks, Stephanie supported our newborn care team with treatment, trainings, and protocol development.

Now, as Haiti is in the midst of both violent political turmoil and a dangerous spike in COVID-19 transmission, Stephanie reflects on her experience at the hospital and shares advice for future volunteers.

Tell us about your experience—how did you jump into your role at the Bishop Joseph M. Sullivan hospital?

Going in, I knew I was going to be at the hospital, but I wasn’t exactly sure what my role was going to be. I knew that I wanted to focus on newborns because that’s my expertise—I’ve been a NICU nurse for almost five years in September.

At the hospital, I was placed with Dr. St Vil. As of right now, he is the only pediatrician in Côtes-de-Fer. During my first couple of days, I mostly observed and asked questions—kind of figuring out what the needs were and how I could help the staff get to where they wanted to be.

I was able to see what our patients were seeking treatment for, which were a lot of babies and small children coming in with skin infections. I was also seeing jaundice and dehydration issues.

What was it like sharing this volunteer experience with your mom, who is from Côtes-de-Fer?

It was so great. I don’t often get to see her in her nurse role, speaking her native tongue, and just completely being herself. It was amazing. It made me very proud that she’s my mother and that I’m in this profession trying to emulate what she does.

“It made me very proud that she’s my mother and that I’m in this profession trying to emulate what she does.”

My mom was more focused on the community health side, where I was more focused on inpatient care and the clinic. But we did get to work on some initiatives together. We did a menstruation demonstration with the students in Grigri—that involved some teaching and distribution of hygiene kits. I was able to go on a few home visits with my mom, and a couple of the community health care workers, too.

You helped develop a discharge checklist for nurses to use while preparing to send new mothers home. How did that project come to be?

I started asking the staff what they wanted to see change and what they wanted to learn. I asked Dr. St Vil, specifically, what he thought we could do to reduce the rates of mortality within the community. That’s the overall goal, as we want to see babies and mothers living and thriving. Dr. St Vil explained that sometimes mothers don’t know what “warning signs” to watch for in order to know when it’s appropriate to seek professional help.

One thing I observed was a lack of education happening when mothers were discharged. Mothers were seeking help back at the hospital a little too late for certain illnesses. For example, there are early signs of dehydration. If a mother can recognize these signs, and know when to bring her baby into the hospital, we can sometimes avoid a serious issue that requires hospital admission and fluids.

Based on these observations and my conversations with the staff, the focus became creating more of a structure to teach mothers and emphasize certain critical knowledge points before they go home with their newborns. We want them to not only thrive at home, but also recognize when treatment at a hospital is needed. So, we created this newborn discharge checklist that mothers are talked through before discharge.

The checklist covers the most critical knowledge points. Things like safe sleep practices, temperature regulation, skin care, infection prevention, and to be watchful if the baby becomes extremely fussy or sleepy—it may be time to come back to the hospital or seek help from a community health worker. I worked in collaboration with Dr. St Vil on that project and it has already been translated in French and in Creole. My mom and I also did some teaching with community health care workers to make sure that we were giving our patients consistent messaging at the hospital and at home.

The other thing that we talked about was simply making sure nurses were allotted time to sit with mothers and teach them to properly latch and feed their babies from the start. If the nurses are there to assist mothers and their infants with a proper first latch, this can help avoid dehydration issues down the road. If a baby is eating properly, the risk for dehydration will go down.

This situation actually happened just prior to my arrival. There was a mom who came in with her baby, who hadn’t voided in three days. The child was severely dehydrated and it turned out that the baby was not latching well at the breast. The baby remained inpatient for a few days, received fluids, the mother received help with breastfeeding, and the baby was able to return home healthy.

What was it like going from such a high-resourced environment to a place like Côtes-de-Ferthat is lacking so greatly in resources? What was that like for you as a professional?

It was distressing at first. I’m used to having babies on monitors so we can keep careful watch on their vitals. I’m used to having everything I need at my disposal. So, it was very different.

For the most part, the staff just works with what they’ve got. But they also rely on their intellect in a way that I don’t necessarily have to do all the time. It was interesting to see and learn from these nurses.

For instance, there was a severely dehydrated baby that came in for treatment. Several people had tried to land an IV on the baby, but couldn’t get it. I can usually visualize where the veins are, but I couldn’t see anything and I was worried. At home, when in doubt, we usually have a tool called a vein finder, which is a light that helps us to visualize veins before poking, but these tools aren’t available here. Soon, a veteran nurse came in. She looked at her anatomical markers as a guide for where to insert the IV. She got it on the first try. That’s not anything that I normally have to do. It’s completely out of my comfort zone.

The way that they rely on their skills is just so different from what we’re accustomed to and I feel like I have a lot to learn from them, and I want to keep learning from them.

“I want to keep learning from them.”

Is there an example you can share where you had to adapt a treatment plan because of limited resources?

A major challenge for the hospital is a lack of medications. Doctors and nurses don’t have access to all the medications they need. For instance, there was a mother who had abrupted, which is when the placenta tears from the uterine wall. It can cause a lot of bleeding and puts the mom at high risk of death. It also threatens the wellbeing of the baby because it can block the flow of oxygen and nutrients.

So, in this case, the baby came out seizing. He had actually been seizing for hours by the time I got there. They did not have the proper medications to control the seizing and the baby was running a temperature. I, along with the nurses, were trying to do everything we could to make the baby more comfortable. An OG tube was placed, which is a tube that goes from the mouth down to the belly. It helps us remove any un-needed air and stomach contents. The baby was placed on IV fluids and respiratory support, nurses were attempting to bring down the infant’s temperature with damp cloths, we repositioned him—anything we could do to make him more comfortable and get his heart rate down and maintain normal oxygen levels.

At this hospital there weren’t really any protocols in terms of what to do when you don’t have the supplies or medications you need. Unfortunately, even more barriers stood in the way, as this hospital did not have a working ambulance at the time nor portable oxygen. With much collaboration among ourselves and the staff, we were actually able to get in contact with the non-profit organization, Haiti Air Ambulance. My mom was able to coordinate getting a helicopter there to transport the baby out of the hospital and to one in Port au Prince that had the proper medication and monitoring needs for this infant.

It was so great to see. The baby is doing well and eating. The mom is also doing much better.

There has been instability in Haiti for a long time, including when you were there. Give us a sense of what that was like for you at that time, compared to what you’re hearing now, following the assassination of Haiti’s president?

In Côtes-de-Fer violence wasn’t really as much of an issue. It seems that most of it was happening in Port au Prince. But it was scary knowing what was going on because I do have family living in Port au Prince. Even then, I didn’t know everything that was going on, but I knew that community leaders were the targets of the violence. There was an attack on a priest, nuns, and health care professionals.

That made me nervous. Because if the violence were to go outside Port Au Prince and into more remote villages like Côtes-de-Fer, my mom and other people at the hospital, including community health workers, would likely be targets—and that’s still a concern now.

It all seems so up in the air. It’s a lot of uncertainty and a lot of prayers on my end.

Do you see yourself going back when it is safe?

Absolutely. I’d love to do more teaching and just have the opportunity to learn and observe more. I also need to work on my language skills. I learned a lot of Creole while I was there but I definitely want to be fluent so I can have deeper conversations with nurses.

What is something you want future volunteers to know?

Go with an open mind and be ready to learn. I feel like a lot of people go into countries like Haiti with the mindset that they’re going to go in and make all these changes without taking people and their culture into account. But just because something works in the states doesn’t mean it’s going to work here.

You really need to understand the culture and take time to observe and listen to what their needs are. They know what their needs are, they just don’t always know exactly how to get there.

“They know what their needs are, they just don’t always know exactly how to get there.”

They just have so much to teach you there, like the IV situation for instance. They have a world of knowledge of their own. They have a lot that they want to learn from you and you equally have so much to learn from them. So, just keep an open mind and take it all in.