Finding Calcutta in ‘The Heart of Nuba’

Mother Teresa once said, “Stay where you are. Find your own Calcutta. Find the sick, the suffering, and the lonely, right where you are — in your own homes and in your own families, in homes and in your workplaces and in your schools. You can find Calcutta all over the world, if you have eyes to see.

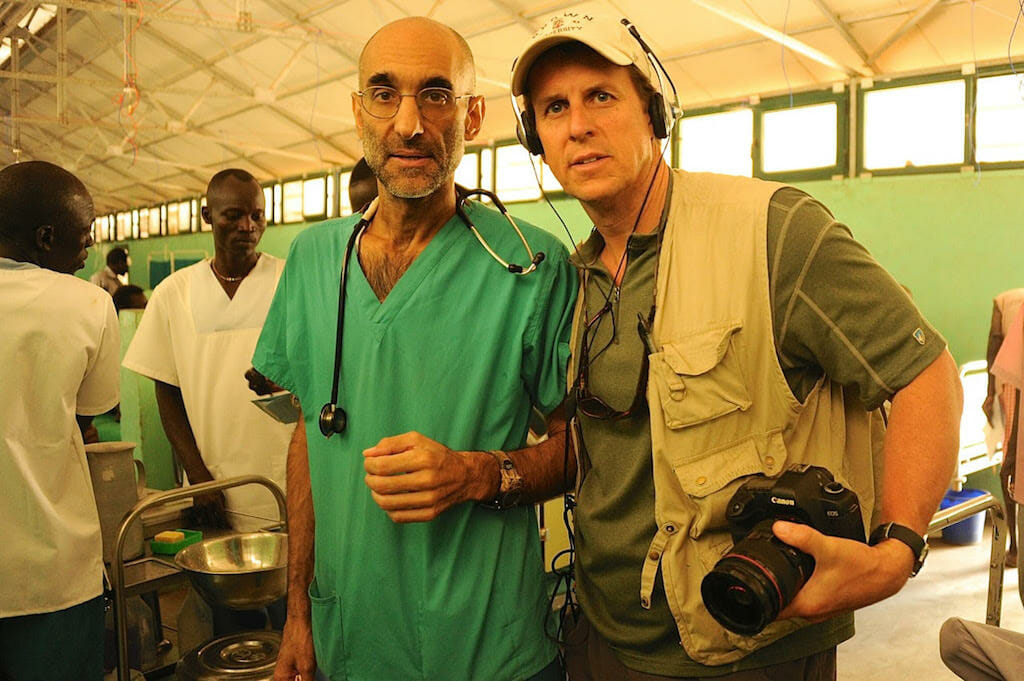

Dr. Tom Catena definitely found his Calcutta in the Nuba Mountains in Sudan, where he has served as a CMMB international volunteer for over 10 years. His remarkable work at Mother of Mercy Hospital in Sudan was captured in the recently released film, The Heart of Nuba. The film was directed and produced by Ken Carlson, his friend and former Brown University football teammate. Ken wrote this piece describing his relationship with Dr. Tom and how he traveled to one of the most dangerous places in the world to capture this important story.

This piece was first published on April 27, 2018 on Truthdig.com

“Catman needs our help,” read the subject line from a former Brown University football teammate’s email. “Please consider donating to our brother, Dr. Tom Catena, in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan. He is the only doctor for nearly a million people who have suffered for decades at the hands of President Omar al-Bashir. Timing is crucial!”

My adrenaline surged. I was transported back to my football-playing days when Tom and I fought side by side on the same defensive line for our beloved Bears. I thought about the bond I had with my former teammates. But what kind of assistance did he need? Was he personally in danger? How could I help?

It soon became clear that a truck heading to the Mother of Mercy Hospital, for which Tom was sole doctor and medical director, was carrying a year’s worth of medical supplies and food when it was hijacked and ransacked somewhere in South Sudan or Sudan. Without these critical provisions, many people would suffer and die, especially with only weeks remaining before the rainy season arrived and all forms of transportation would come to a screeching halt. This felt like the fourth quarter of a tense game, except this time it was fourth-and-one on the goal line and a matter of life and death.

Within three weeks, the Brown football community raised more than $102,000. A new truck was purchased, then filled with even more foodstuffs, vaccines and medical equipment than the original one. The truck made it to the hospital just two days before the heavy rains of Sudan began to fall. Dr. Tom had his patients’ backs, and we, in turn, still had his.

This got me thinking: If not a film, what could I do to help? Tom said without hesitation: “Mother Teresa was asked what an ordinary person could do to help build a better world. She answered: Find your own Calcutta. Find the sick, the suffering, and the lonely right there where you are—in your own homes, in your own families, in your workplaces and in your schools. You can find Calcutta all over the world if you have the eyes to see.”

Not the reply I was expecting from a former monster of the gridiron.

His rebuttal knocked me back. Those very words of Mother Teresa have deeply affected me since childhood, and although I’ve tried to use them as a guide for my life and my work, I didn’t realize until then how profound an impact they truly have had on my life.

A little background: I come from a family of ministers going back to my great-grandfather, so the idea of having a calling to help people is ingrained in my DNA. I learned empathy, and truth be told, I didn’t know there was any other way to live one’s life. My father taught my brother and me that helping others was the greatest calling one could have.

So when one of my wife’s family members was senselessly murdered in the early ’90s, I was prepared to counsel my loved ones through their grief. Though I was helping others get over her death, I’m not sure I ever did. I decided to channel my own grief and loss by taking a position with the television show “America’s Most Wanted,” where the host, John Walsh, used television to bring fugitives and murderers to justice.

I went from producing and directing TV episodes to making documentaries, always looking to make a significant impact. But honestly, none of my films changed the world. As I have learned, life can have a way of distracting us from “finding our own Calcutta.”

I was struck by this realization when I reconnected with Tom at that Manhattan café and became aware of just how different our lives had become. I moved to California to make movies. I married my college sweetheart, had three children and have done well in business. Tom went into the Navy, attended medical school, remained single and moved to Sudan, where for the last decade he has devoted his life to being a surgeon at the Mother of Mercy Hospital in the Nuba Mountains. (I had no idea where the Nuba Mountains were located.)

It became clear that I needed to put aside Tom’s humility and move forward on making a film. The more research I did, the more I became inspired by Tom’s life, by the immense sacrifice he made by moving away from his family in upstate New York and his unwavering dedication to his work. I became convinced his story, and the story of the Nuban people, had to be told.

For more than five years, Sudanese President Omar Hassan al-Bashir has been bombing civilians in his country’s Nuba Mountains, resulting in an indictment by the International Criminal Court on 10 counts of war crimes, including crimes against humanity, as well as genocide in Darfur.

He is a wanted criminal, yet he travels freely outside of Sudan, avoiding capture.

Nuba should be as familiar to people around the world as Darfur, but it is largely unnoticed. It is not of strategic value to the U.S.; it doesn’t export much oil and has very little gold. Part of the reason people aren’t aware of this genocide is because the government in Khartoum doesn’t permit visitors, including foreign humanitarian workers of any kind, and especially people like me—filmmakers and journalists.

These conditions present a huge challenge to Dr. Tom, as he is fondly called by his staff and patients. Tom does everything from training his staff to working seven days a week, from delivering babies to treating amputations and lacerations that result from the bombings. He is the only surgeon in that entire war-torn region; taking a day off can mean death for one or many patients.

Two-time Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist Nicholas Kristof of The New York Times has reported that, in Sudan, Dr. Tom has been compared to Jesus Christ. This does not exaggerate how people feel about him.

The more I learned about what Tom was doing, the more determined I became to tell his thrilling, yet heart-wrenching story. I embarked upon my first journey to the Nuba Mountains to persuade Tom to allow me to make a feature-length film. He said if I made it all the way to him in southern Kordafan, he’d consider cooperating. No promises, though. Little did I know how difficult getting to him would be.

Since President al-Bashir doesn’t allow filmmakers or international journalists into Sudan, I had to be smuggled across the border from South Sudan. During my first trip, while I was standing next to the plane on a dusty airstrip in 115-degree heat, I was surrounded by boy soldiers, many of them around 12 to 16 years old, some even younger.

Robbed of their innocence, these child soldiers were not playing with toy guns. They were pointing fully automatic AK-47s directly at me. In a matter of seconds, but what seemed like an eternity, there was a flurry of shouting, shoving and spitting on me. These kids were close in age to my own kids, yet their reality was much different. They were hardened soldiers ready to take measures into their own hands.

I realized those moments might be my last. I could die on that airstrip in South Sudan. Finally, out of desperation, I mentioned Dr. Tom’s name and the mayhem stopped. Literally stopped.

“You know Dr. Tom?” one of the adult soldiers asked. I said “Yes! We are close friends. We attended university together, even played on the same American football team together!” After much discussion, miraculously, I was released, allowed back on my plane without further incident. The pilot asked if I knew how lucky I was, and I readily agreed.

“No,” he said. “Do you know how truly lucky you are? Two weeks ago, 26 people were taken off this very cargo plane, dragged to the corner of the airstrip,” he said, pointing, “and had their throats slit, left to bleed out, to be eaten by wild animals, the lowest form of death in Africa.”

At that moment I began to understand the meaning of the film I was hoping to make: Dr. Tom is so critically important to the survival of so many people—and so loved by them—that the mere mention of his name saved my life. Also at that moment, Tom’s words—“If you make it to me”—took on greater heft. On the hellish drive in mud-covered Land Cruisers into the remote Nuba Mountains, we dodged several barrel bombs dropped by Soviet-built Antonovs.

Upon arrival at Mother of Mercy Hospital, Tom gave me what I remembered as an All-American nose guard hug, although almost immediately, whatever excitement and optimism I felt on this quest was quickly “bombed out of existence.” Seventeen casualties arrived at the hospital, the latest victims of government bombings in the region. Dr. Tom, always on call, switched into scrubs and high gear. Cameras came out and we started to film. The “we” was just me and the only cameraman out of Nairobi I could find with enough courage, or perhaps stupidity, to accept the assignment.

Nine of those casualties were kids who had been sleeping in their tukul, a thatched hut, in a small village when an artillery shell exploded nearby. Three were burned to death immediately. Six traveled more than 25 miles on foot to the hospital with second- and third-degree burns. Three of them died within 24 hours.

A 7-year-old boy, Shanta, was one of the survivors. More than 70 percent of his body had third-degree burns, a burn so severe it penetrates deep tissue and chars the skin. I sat with him, prayed over him, talked to him about life. His only response was, “Omi, Omi”—which translates to “My mother, my mother.” It broke my heart.

Seeing my willingness to help, Tom eventually, although reluctantly, gave me clearance to make a film. Even with his approval, it took about a week of begging before he granted me an interview. I asked many questions. He offered articulate yet passionate answers. Our conversation continued to come back to the plight of Shanta and those like him. We both were devastated.

To see a child suffering like that, the life draining out of him, to think of your own children in that moment, is heartbreaking. Shanta had a will to live I have never witnessed, but Tom had seen it over and over. For close to a month, Tom daily cleaned Shanta’s maggot-ridden scabs (which hatched hourly) as the boy fought to survive. Ultimately, his will was not enough, and the resources of the hospital were too limited. After three weeks of shooting, I had to leave Tom and the Mother of Mercy Hospital. Shanta died the next day. His death affected me to my core. Here was a kid who was simply born in the wrong part of the world, killed by his own government. I would not let his story die. I couldn’t go back to my life in California and forget what I had experienced.

I knew, as a documentary filmmaker, that this was a life-changing experience, an opportunity to not just tell a true story but to help change the ending. The success of this movie would not be measured by its financial outcome or film critics’ reviews but by its potential to save lives.

That goal was aided just last year, when the former Sudanese ambassador to the United States and majority leader of the Sudanese Parliament, Mahdi Ibrahim, agreed to travel to California to meet me and to see my film in my home.

As the final credits ended, this impressive man, who struck me as a cross between Martin Luther King Jr. and James Earl Jones, wept uncontrollably. He said he had no idea the real effect the bombing by al-Bashir was having on his own people, that he was both “shocked and ashamed.” He promised to put an end to the death and destruction. He would make stopping the bombing of his brothers and sisters his number one priority.

A few days later, upon returning to Sudan, Mahdi told me that he brought the film directly to President al-Bashir and screened “The Heart of Nuba” for him to witness the real devastation of the bombings. Less than two weeks later, I received a call from Mahdi announcing that al-Bashir was deeply moved and had ordered a suspension of all bombing in the Nuba region, which has lasted over 14 months now. I don’t know if he was so moved by the film or if there were other motivations involved. In the end, I honestly don’t care why, only that it has stopped.

This I do know—there have many organizations, including Amnesty International, Enough Project, Act For Sudan and Catholic Medical Mission Board, and individuals like Dr. Tom and Ryan Boyette of Nuba Reports that have been tirelessly working to expose the conflict in this region and to ultimately improve the lives of the people living in the Nuba Mountains. “The Heart of Nuba” has stood on their broad shoulders to achieve a tipping point resulting in the cessation of the bombing.

Contributing to the cease-fire, which could end at any moment, is very important, but accomplishing peace on a permanent basis and creating a humanitarian corridor to get aid into the people Nuba Mountains is another. So, through contacts I had made, I reached out to President al-Bashir and asked if he would allow me to interview him. Much to my surprise, and the dismay of my wife and three children, he agreed.

In September 2017, I found myself in the capital of Sudan, sitting face to face with the villainous antagonist of my film, in search of answers to the many questions that Dr. Tom, the people of the Nuba Mountains, and I had. What I discovered through this surreal interview process was, as Hitler once said, “If you are going to lie, lie big and lie all the time.” Al-Bashir denied all wrongdoing, blamed the carnage in the Nuba Mountains on “friendly fire,” and was greatly relieved when the interview concluded. As was I.

Safely back home in California, I was reminded that documentary filmmaking is always about discovery. In the research, in the field and in the editing room, one learns something every step of the way. In that sense, it’s a wonderful metaphor for life. Our lives are all about discovering our own purpose and committing to that final cut. In the heart of the Nuba Mountains of Sudan, I discovered my heart, that sense of purpose of my father the minister, though I realized his frustration in being able to reach from his pulpit only those who showed up in the pews on any given Sunday. A documentary can reach millions.

Through the course of this project, I made two harrowing trips to Nuba and one to Khartoum. The three trips totaled just under seven unforgettable weeks. In the end, I left the perilous region of Sudan having “gotten” the story. Tom, who is as close to a saint as anyone I could ever hope to meet, stays to assist others as they struggle to survive. My concern for Tom endures, but regardless of the hardship, Dr. Tom is exactly where he wants to be. He reminds me that his greatest compensation is the fulfillment and peace that comes from serving others in need—he found his Calcutta. There is a lesson in that for all of us.