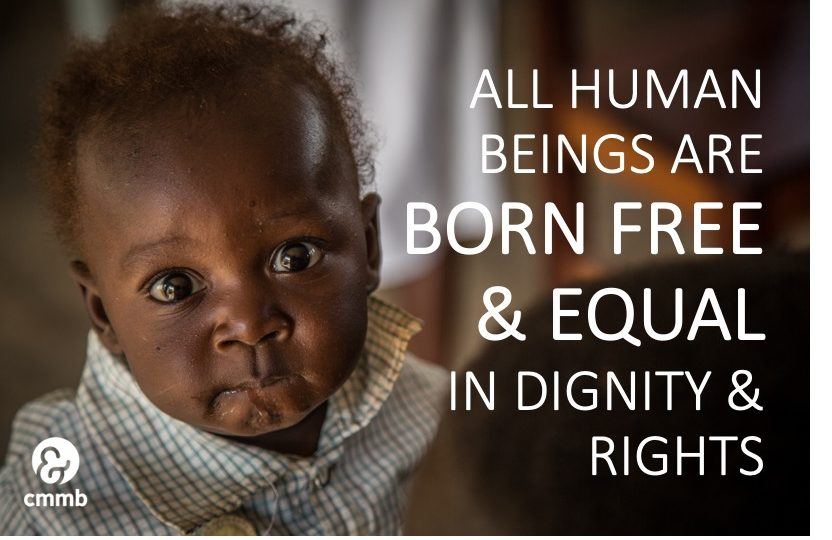

The Most Basic Human Right: The Right to Life

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights turns 70

December 10th is Human Rights Day. 70 years ago today, the United Nations General Assembly adopted the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, a milestone document that proclaimed the inalienable rights which everyone is inherently entitled to as a human being — regardless of race, colour, religion, sex, language, political or other opinion, national or social origin, property, birth or other status.

In this piece, Dr. Matthew Jones– a volunteer who served for nine months in South Sudan – writes about the most basic right, the human right to life.

Working as a doctor in South Sudan, one becomes accustomed to the speed with which the calm blue skies can cloud over, a sudden wind picking up and a downpour drenching everything through to its core. The calm of the wards carries a beauty and peace, a sense of an Eden before and after the world of technology and anxiety.

But in a land with minimal organised healthcare, such Eden can become a nightmarish desert, a land of desperation and cruelty with alarming, shocking speed.

One day, a Sunday, I was working on the ward seeing the few new arrivals, a series of children with malaria, none of whom worried me, admissions that would last a few days before we could send them home recovered. The staff were relaxed, a slightly frivolous air, playful and light.

The first sound of trouble in the hospital is often the low drone of motorbike engine, as the bike arrives at the hospital gate. Invariably, the bike will carry 3 people, the middle one the invalid. That Sunday morning, as I stood outside the ward, watching the approaching motorbike, a foreboding set in, the sense that it could contain anything or nothing.

The term human rights, has become a strangely politicised entity in the West, bringing to mind issues of identity, self-expression, and cultural belonging; bringing to mind the complicated debate about how far the collective seems willing to go to tolerate complex personal expressions of being. Somehow, it increasingly associates with issues of gender, sexuality, race, and how the perceived minority and majority cultures interact.

Spending time serving in South Sudan as a doctor has reminded me of the most basic identity, being alive, and the most simple expression, living free of disease, the human right to life.

When the motorbike stops, the staff quickly assist the passenger and driver, the bread in this morbid sandwich, in bringing the invalid into our duty room. The routine of presenting this way often carries a slightly theatrical air, a young person, suffering from malaria, anxious, a degree of somatisation and performance. But this time, there is no theatre, no hysteria, no rolling of eyes in the knowledge that the next day, the person will have recovered miraculously.

On cursory inspection, it is clear that there may be no tomorrow for this patient. It is a middle aged woman, deathly thin, a gaunt face of almost surreal quality; unconscious, unrousable, untouchable almost in her state. I have never seen a person closer to death outside of a hospital bed.

The passenger is her husband. The story heartbreaking. The woman became ill 5 days ago, in neighbouring Congo. They attended a clinic, already 20 miles from their hut, where she was diagnosed with HIV, clearly in advanced stage. They simply continued on their journey on foot, seeking medical care across the border. Not for the first time, I wonder how desperate a country’s healthcare must be for its citizens to seek treatment in South Sudan.

The journey appeared to have lasted four days, an unimaginable trek across jungle tracks, without food or much water. When they finally arrive at our doors, the woman is so dehydrated, almost mummified; the husband appears to be upright from sheer will to see his wife treated. I notice him later, quietly slumped against the wall of the ward. I give him a glass of water and sugar, which he gulps down before I’ve even left his presence. I repeat the gesture.

The oldest identity: alive; the oldest expression of being: a beating heart and breathing lungs.

It is wrong to think that life in South Sudan is qualitatively different from life anywhere. Even in this troubled land, people love, people work, people gather; the way they have for thousands of years; the way we have. It is more recognisable than different, beneath the simple clichés of cultural difference.

Indeed, life in the town of Nzara, where I have been working, carries a joy and beauty to my eye that can feel lacking in the West. A default of friendliness, openness and community; so little trace of the coruscating anxiety and debilitating depression that stalks the West, the modern day equivalents perhaps of war and famine.

Dr. Matthew Jones with two clinical officers, Moses and Joseph, at St. Theresa Hospital in South Sudan.

But, the quantity of suffering, of death, of morbidity is necessarily greater here. Put simply, when things are bad here, they are very bad. People don’t present with minor cuts and infections; they present with the deepest and foulest of infections; we don’t catch illnesses when they are theoretical medical concepts, but often when they have already done their best and their worst to the human form.

Sarah Rubino, international volunteer nurse and midwife, spends time with a young child who was badly burned by cooking oil.

Doctor on call. While spending time visiting communities in Yambio, Dr. Matthew Jones gave care to a young girl.

The woman is carried into our duty room. We quickly assess her, the low blood sugar, the dehydration, likely a serious chest infection compounded by HIV/AIDS. There is a moment when one wants to wrap her in a blanket, place her in a bed gently, and allow her to slip away from her own suffering. But her husband is there, staring on, mute, terrified, his eyes filled with the opposite of love, despair. Whatever this woman is to us, to him she is simply the woman he has known and loved and raised children with most of his adult life.

And so we work. We tackle the problems slowly, steadily. Not just the medical ones. We clean her up, a catheter in place, soiled clothing removed. She receives intravenous fluid, antibiotics; basic pain relief. It suddenly feels not futile, but an act of restoration. Her face gains a little colour; her blood pressure is recordable now; pulse stronger, breathing stronger.

The final right, to die with dignity, in a place of compassion and care, in a place that gives up on no life.

Hope, restoring life a little, a chance of a tomorrow.

Human rights. The human right. To life. To exist in a society that cares about your welfare, that provides care in your darkest hour, no matter how little light remains of the day.

The woman died the same night. She slipped away without ever regaining consciousness. The husband slept in the ward nearby that night. The following morning, he returned to the Congo, his wife’s body buried near the hospital, no means of reversing the tortured journey. He’ll return to his life, his family, alone.

Human rights. The final right, to die with dignity, in a place of compassion and care, in a place that gives up on no life. The right to watch society pull together to care for your loved one.

The oldest identity: alive; the oldest expression of being: a beating heart and breathing lungs.