Martin Reflects: Lent in South Sudan

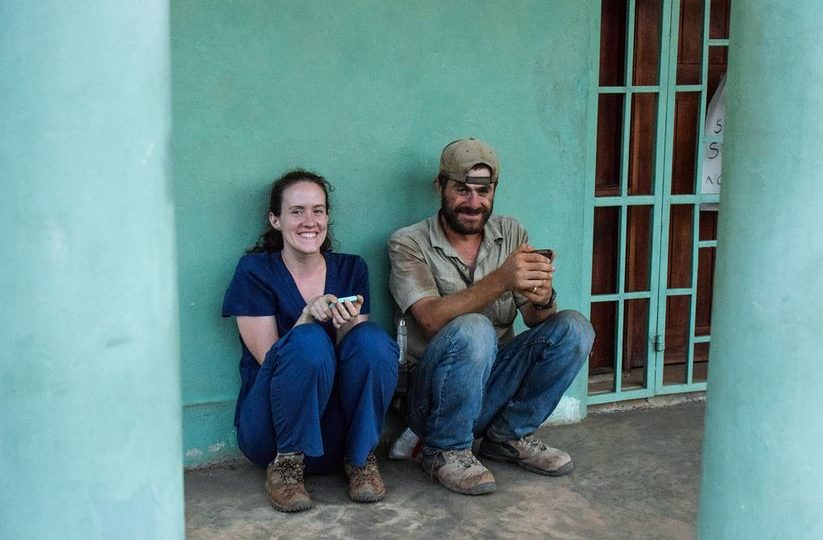

Martin Rubino and his wife, Sarah, are long-time professional volunteers with CMMB. As an engineer, Martin helped lead a lifesaving hospital expansion project in Nzara, South Sudan. Sarah, a nurse-midwife, has helped countless moms in this close-knit community safely welcome their little ones into the world. Now, they’ve returned to this same community of Nzara for a third time. Arriving just before this faithful season of Lent, Martin shares a reflection on the meaning of Lent and life with his family in South Sudan.

My family arrived in South Sudan shortly before the beginning of Lent this year. It is the third time my wife Sarah and I have gone to live and work at St. Therese hospital in the village of Nzara. It’s our son’s second and our little daughter’s first experience with the people and culture that have kept drawing us back since our first trip five years ago.

Life in Nzara is understandably much different than life back in the United States. As you might expect, there is a lot of need across the board, from food and healthcare to education and opportunity—you name it. Yet there is also a vibrancy and a sense of peace here, and our reasons for returning were as much to experience these aspects again as they were to serve the needs.

Coming to Nzara from the affluence of the United States, you are confronted with the tension of trying to hold apparent contradictions together. On the one hand, modern life affords us choices, technology, financial security, specialized healthcare, and everything else we employ to protect ourselves from want and lead efficient, productive lives.

At the same time, however, we can be overwhelmed by the choices and tech constantly in front of us, or grow so worried about work and the future that we lose sight of what is most important around us in the present. Life in Nzara is simpler and slower. Basic tasks like cooking and washing clothes take nearly all day. People must live day-to-day because the food will spoil and there is no money left over to save.

If you had to choose one word to characterize the community of Nzara, that word would almost always be closer to “joyous” than to “miserable.” You often hear people chat and laugh together while going about the daily chores. I don’t mean to romanticize or sugar coat the difficulty of their lives. “Living simply” can just mean that children go without adequate nutrition. “Living in the day-to-day” often translates to families facing the gnawing uncertainty of there being food tomorrow, or the day after tomorrow, or next week. “Living joyously” can mask the heartbreak mothers and fathers feel when a child dies in their arms. It’s the tension, the contradiction, I cannot resolve.

Life in Nzara is indeed much different than life back in the United States. In many ways it cannot be compared, though I don’t think it needs to be. Sarah and I come from a different world than the people here, and this will be true no matter how many times we return, or how many strong friendships we have enjoyed here over the years. Even so, those differences are not absolute. The connections we have made and the welcome we have received are undeniable and tangible. It would be a mistake to conclude that these hard, hidden lives have nothing to offer the rest of the world.

Are we grateful for what we have while, at the same time, recognize that even a thoroughly modern life, one with nearly everything only clicks away, has its limitations, and comes at a greater cost than we tend to think? Is it possible to appreciate the quality, variety, and convenience of the material things we have, but not allow them to disconnect us from those around us? Can we be thankful for our resources to plan ahead and eliminate many of life’s uncertainties, but not fall into a false sense of self-sufficiency, or become so worried about the future we lose sight of that which is most valuable? Are we able to maintain peace and joy even if we cannot avert all the suffering and tragedy in our lives and in the world?

This Lent, let us keep in mind that Christianity holds as true many facets, which, from our vantage point, appear to be in contradiction. But they would nevertheless turn unrecognizable if we attempted either to fully resolve or fully separate them. The people of South Sudan do not get choose their sacrifices, nor do they get a respite after Easter. This Lent, I will pray for them.