On International Day of Education Let’s Learn From Each Other

Today is the first ever International Day of Education, celebrating the role education plays in peace and development. There are so many things affecting the health and well-being of women and children around the world. A lack of resources, education included, locks children into a cycle of poverty. At CMMB, we know the importance of education when it comes to empowerment and sustainability. Our female empowerment programs in Haiti and Peru educate women to be both financially responsible and practice healthy habits in their own lives, and in the lives of their children.

One of the reasons these programs have become so critical is because as children, so many young girls do not have the opportunity to receive a formal education.

“Education is the most powerful weapon which you can use to change the world.” – Nelson Mandela

To celebrate this important day, we asked one of our dedicated and committed international volunteers, Angela Barratt, to share what she has learned about education and peace in South Sudan. Angela, is currently serving as a supporting teacher at St. Mary’s Catholic School in Yambio, South Sudan. Her stories and reflections have offered insight into the relationship between education and healthy lives. The following piece is no exception. In it, Angela shares an interview with a remarkable woman, who she has had the opportunity to teach beside at St. Mary’s.

The First International Day of Education

In December, the UN General Assembly proclaimed January 24, 2019 the first International Day of Education.

“And we look at the International Day of Education as a day of reflection… but more importantly, as a day of learning; learning from each other.” -Burhanudeen Gafoor

Without inclusive and equitable quality education and lifelong opportunities for all, countries will not succeed in breaking the cycle of poverty that is leaving millions of children, youth and adults behind. We will not succeed in mitigating climate change, adapting to the technological revolution, let alone achieve gender equality, without ambitious political commitment to universal education.

This day is the occasion to reaffirm fundamental principles. Firstly, education is a human right, a public good and a public responsibility. Secondly, education is the most powerful force in our hands to ensure significant improvements in health, to stimulate economic growth, to unlock the potential and innovation we need to build more resilient and sustainable societies. Lastly, we urgently need to call for collective action for education at global level.

– Message from Ms Audrey Azoulay, Director-General of UNESCO on the occasion of International Day of Education

Education and Peace

According to the Global Peace Index, only Syria and Afghanistan have less peace than South Sudan (2018) (I recommend checking out the Index; the map may surprise you). Education and peace in Yambio seem to me a bit of a chicken-and-egg problem right now.

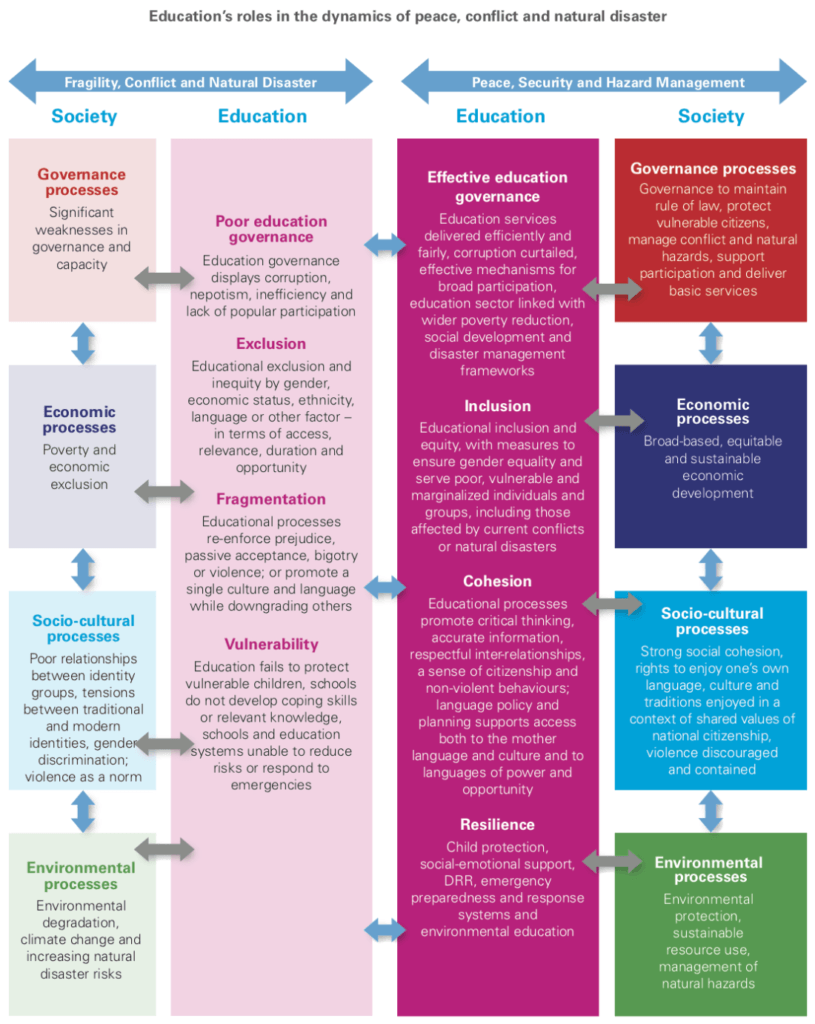

The above figure was created to illustrate some of the interplay between education and destabilizing factors in Southeast Asia and the South Pacific, but I think it does a good job of highlighting ways in which education touches other spheres, as well as some of the breakdowns in education in the midst of fragility.

But, what a chart can’t show is that even in the midst of fragility, there are amazing people fighting for education: to teach, and to be taught. Flora* is my best friend and closest ally at St. Mary’s Primary School. She is tough as nails but so kind, looking after everyone who needs it (including me!). She is not “educated” in a Western sense but she is a truly dedicated teacher, one of the few who are there every day. She teaches one of the three primary One classes. I asked if I could interview her so that I could learn her story and share it with others.

*We agreed that I would use a pseudonym. I recorded our interview and transcribed it, and have lightly edited quotes for clarity.

Learning From Flora

Flora was born in Yambio but fled to the Central African Republic (CAR) with her mother and siblings when she was about six years old (in 1990 or 1991), at a time when the Sudan People’s Liberation Army (SPLA) was in control of much of the area. I ask her if she remembers anything from before the move, and she says no, but that she was told she and her twin sister cried on the long journey by foot.

“My mother found somebody on the way to help carry us on his shoulders. When he reached his place he put us down and we started crying.”

There was a large refugee community where she was living, and she grew up speaking Zande, Arabic, and French (the language of primary school instruction in CAR). Her father stayed behind in Yambio for another five years or so, continuing his business as a carpenter and helping his father look after things. I ask if it was harder for her to go to school since she was a girl, and she says “No, the problem was just poverty.” Alongside her siblings, she sold mandazi (think large, unsweetened doughnut holes), cassava flour, and firewood to raise money for education, but it was not enough. “I was interested in learning, and the problem was I had no one to support me. That is why I got pregnant early.” While it is common here and there for teachers to have their infants with them, schools do not allow students with nursing babies to attend. She was forced to drop out of Primary eight to take care of her son.

Slowly, people began to return to Western Equatoria, and Flora returned with her whole family in 2007. She was part of the inaugural class of students sitting for P8 exams in Yambio after many of the refugees had returned. She completed her Secondary Schooling, in English, in Yambio.

Flora was not planning to be a teacher. “What made me a teacher is that I didn’t have any other work to do,” she says. “But the work of a teacher is good, that’s what made me decide to be a teacher. When I was going for my teacher training, it touched my heart.” She loves that for teachers, learning is never complete.

I asked Flora if she could tell me any stories. She brought in this handout from a training long past that outlines a story from nearby Kenya

The teacher training college in Yambio is referred to as “Solidarity.” Solidarity with South Sudan is a faith-based organization that has been in South Sudan since 2008 and are a big part of the community here in Yambio, and across many parts of South Sudan (check out this presentation from their website; it not only shows some of the awesome work they are doing, but it also gives a really good picture of city life in Yambio).

Training at Solidarity was free for Flora, but not easy. The program is a two year residency on campus, and Flora had young children to take care of. Some people expressed doubts about her ability to do both. Solidarity is a competitive program for student teachers from all over South Sudan, requiring an interview for admission. At her interview, Flora was told that since she had young children and they were in Yambio, she could stay with them at home as long as she could be ready for training at 7am. While the other students were living at the school, Flora slept at home with her children, to ensure they went to school. She explained, “Because if [she] left them at home, no one would tell them to go to school.”

“I got up very early in the morning,” she tells me, “At five, and swept my compound, got water for my children and made them tea. After they had tea, they started off for their school, and I went to mine.” One of her sons, too young for school, went with her to Solidarity and spent his days with the watchman.

Thinking back on my own education and the freedom I had, I tell her I think she is amazing, and that it sounds like a lot of work. “Yeah,” she responds, “It is a lot of work for two years.”

Not that being a teacher here is any walk in the park, once training is completed. There are so many challenges, particularly for women, that I hope to write more about later. I ask Flora what girls at our school want to do when they grow up, if they want to be teachers or work in government or only get married. Flora answers, “Some of them, they don’t want to be a teacher, because they say that the work of a teacher is very hard.”

“They are right!” I respond, laughing. “Yeah,” she agrees, also laughing. “Yeah.”

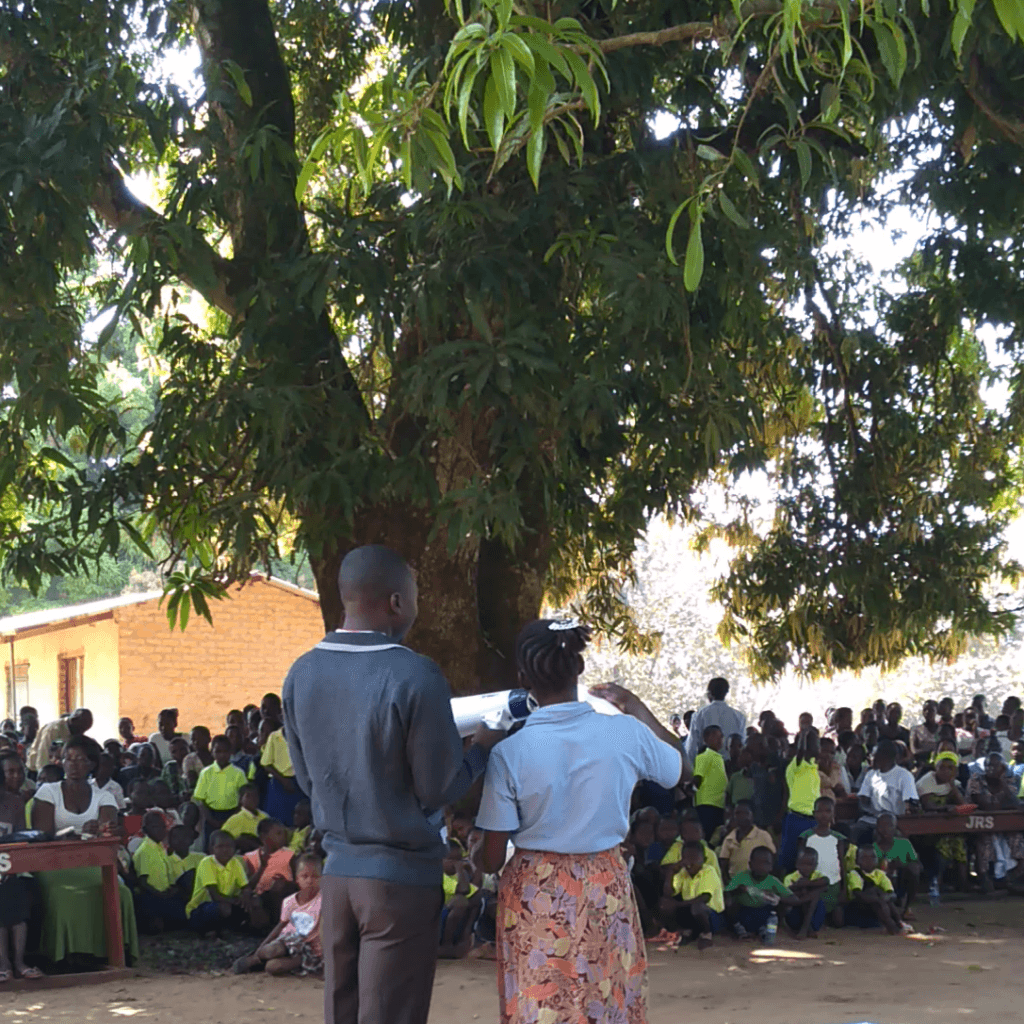

Flora and I chaperoned 30 female students to Yambio’s march for the 16 Days of Activism against Gender-Based Violence Campaign

Flora would like to go to University. “In Juba?,” I ask, knowing that institutions of higher learning are at least that far away. She responds that Solidarity is in the process of creating a three-year diploma program here in Yambio. That would mean a lot to Flora, who wants to wait until her youngest child is around 12 before taking up her studies again.

I ask her what she hopes for her children. She responds with a small chuckle, “I want all of them to finish their education, if I have the power.”

I ask her what she hopes for her country. She responds that, “The only thing I have been hoping for it is peace. If there could be peace here it could be very nice.”

Angela Barratt is serving in Yambio, South Sudan for seven months. A native of Houston, Texas, Angela earned her bachelor’s in anthropology through the University of Texas’s Plan II program, and her MSIS from the University of Texas School of Information. Thank you, Angela for your dedication to the community you serve. We love sharing yours stories.

If you are interested in learning more about international volunteer opportunities, click the button!