World Health Day: Kerima’s Story

April 7th is World Health Day. It’s an opportunity to come together as a global health community to share stories and raise awareness about the challenges people face in their search for healthcare. This year, the World Health Organization is celebrating its 70th anniversary. It is calling on all world leaders to live up to the promises they made when they agreed to the Sustainable Development Goals in 2015.

In this piece, international volunteer and Aurora Fellow, Dr. Matthew Jones, tells the story of one six-year-old girl in South Sudan. Her story shines a light on all the obstacles that stand in the way of accessing essential, life-saving care, especially for those living in the most remote places in the world.

The monthly staff meeting at St. Theresa Hospital lasted about an hour. It began with a review of the previous meeting, then covered a series of administrative issues, mostly minor, of concern to exasperated hospital matrons everywhere: inappropriate footwear, unclean toilet facilities, poor documentation, the challenges of impressing upon healthcare staff the importance of attention to detail.

Sitting in front of me is a six-year-old girl. She is upright on a couch, seeming to hang on to every word of the meeting. In addition to serving as the meeting room, staff room, and drug preparation room, this space is also home to the only high-dependency bed in the hospital. The little girl, Kerima, has been on the ward for six days and this is her story, or the beginning of it anyway.

In early March, Kerima was admitted to St. Theresa’s generally unwell, with significant, recent weight loss and increased thirst. It didn’t take long for clinicians to diagnose Type 1 Diabetes Mellitus (T1DM). But the challenge of managing such a chronic, incurable condition will remain with Kerima, her family, and the wider healthcare community here in Nzara, for the rest of her life.

Kerima lives in one of the most unstable countries in the world—the third poorest—where access to even basic medical supplies can be limited.

I was due to meet Karima’s mother, Halima, to begin to prepare for Kerima’s discharge from the hospital. There is a long list of issues that need to be discussed with newly diagnosed T1DM patients as early as possible. I needed to explain that this little girl:

- Will require a minimum of two injections a day of insulin and two finger prick tests of her blood sugar levels.

- Is at risk of acute crises, called diabetic ketoacidosis, particularly if she has another short term disease like a chest infection.

- Is at risk of low blood sugar levels if she receives too much insulin. Both these crises can kill her.

- Longer term, without excellent control of her blood sugar levels, and even with—as we are coming to discover in the west—she will spend the rest of her life at increased risk of damage to her eyes, nerves, kidneys, and increased risk of heart attack and stroke.

How to even begin this conversation with Kerima—and more importantly—her family? How much information can you even begin to pass on?

“Health is a human right. No one should get sick and die just because they are poor, or because they cannot access the health services they need.” —Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus, Director-General WHO

First Meeting

The first meeting I have with Halima is delayed by several days, due to poor mobile phone signal, confused translation, and missed messages. St. Theresa Hospital in Nzara is run by the Comboni sisters of Italy. The hospital has a reputation of such excellent care and service, that patients travel from many miles away, even across borders from neighboring Congo and Central African Republic to receive care. Kerima’s mother travels approximately 13 miles to reach Nzara. It’s a costly journey that takes Halima away from her work. As a result, she cannot be at the hospital every day. In her place, Kerima’s grandmother has been sleeping nearby, coming into the hospital to care for Kerima, cooking food on-site, and helping wash and change her granddaughter’s clothes.

At medical school, we are taught to begin by finding out what Kerima’s mother knows about T1Dm. This is the summary I would offer an educated patient in the UK:

Type 1 Diabetes mellitus is an auto-immune condition which has no direct, identified cause to explain why the body begins to attack certain of its own cells within the pancreas – cells which are normally responsible for the production of insulin, which converts sugars we eat into more useful and storable forms. Without insulin, the sugar remains in the blood. It is excreted as urine through the kidneys, and unable to access the sugar, the patient starves to death.

It is a different beast altogether from Type 2 diabetes, which is characterized broadly as a lifestyle illness due to poor diet and increasing obesity. It is most common in the West, though inevitably its incidence is increasing through the world wherever the Western diet – high in calories, sugars in particular – is introduced. Type 2 diabetes does not necessarily involve complete failure of the system and many patients will never need replacement insulin. There is increasing evidence that a strictly implemented diet can bring the disease under control or even send it into remission.

Type 1 diabetes, however, requires constant attention, in the form of daily injections, daily skin prick tests of sugar levels, and routine surveillance for complications, including kidney failure. T1DM is the most common cause of chronic kidney disease, transplantation needs, blindness, and nerve damage. Nerve damage can cause foot deformities and ulcerations and can even require amputation.

A Difficult Conversation

I speak to Kerima’s mother. Halima’s English is basic but she understands me sufficiently. Indeed, as I stray into patronizing her she says calmly,

“If I don’t understand, I will say.”

I proceed.

“Diabetes is a condition that Kerima will suffer from all her life.”

“All?”

“Yes. What that means is that she will need an insulin injection every day and blood sugar testing.”

Halima looks at me with what might be horror, certainly surprise.

“She will need injection every day?”

Care Required

The minimum treatment for a patient with T1DM is finger prick testing of blood sugar levels, twice daily insulin injections with a needle in shallow body tissue (usually in the stomach) with thorough skin cleaning before and after. The machine to test blood sugar levels needs to be maintained and repaired if it malfunctions. Needles and skin cleaning solution need to be disposed of safely, every day. Insulin must be stored in a fridge, which Halima does not own. It’s worth noting that there is no central electrical grid in this part of the world. The hospital relies on solar power.

In order to manage Kerima’s disease, a family member or ideally more than one, will need to become experts in the operation of this daily system, delivering injections, testing blood sugar levels, and spotting signs or symptoms of approaching crises, including high or low blood sugar levels, which can kill very quickly. There is no respite from T1DM and there are few resources available to assist Kerima’s family here. The practical consequences of T1DM are overwhelming even in a Western setting, where every healthcare professional has seen the difficulty in keeping children and young adults compliant, cooperative, and hopeful in the face of their condition.

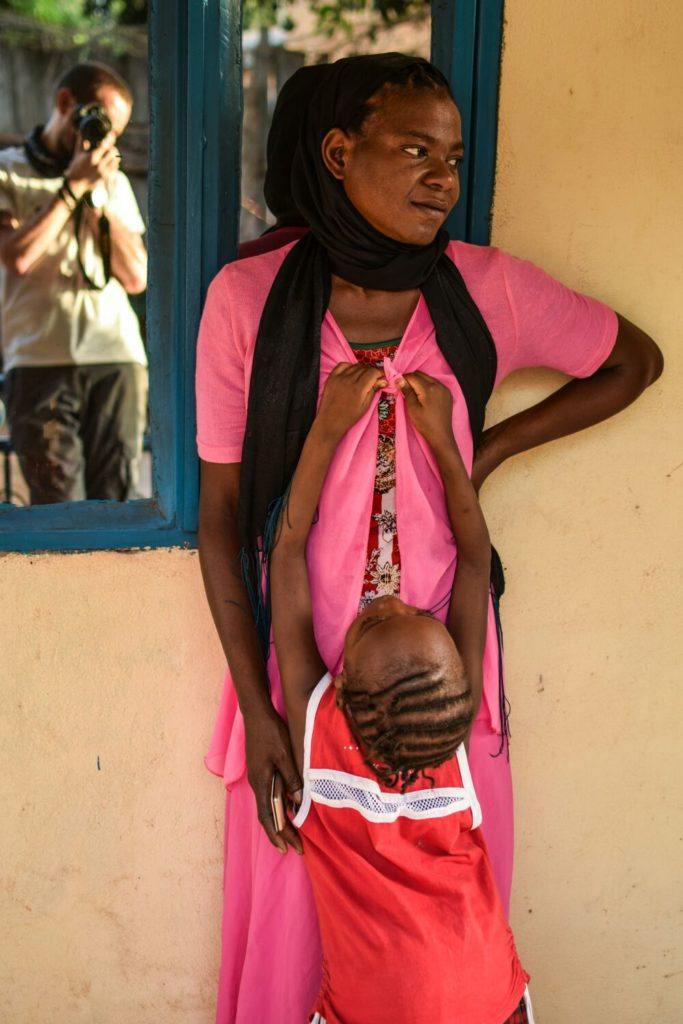

Kerima and her mom Helima at St. Theresa Hospital in Nzara, South Sudan. CMMB volunteer and author of this piece, Dr. Matthew Jones, is caught in the reflection.

The Conversation Continues

I ask Halima about her circumstances. Halima has two other daughters, both of whom are well, but sadly the father is not present. Her first husband was killed in fighting across the border in Congo. Kerima and her younger sister’s father did not stay with the family because in her words, “He wanted a boy and was not interested in girls.” Halima tells me that a local elder is the only male support she has, though her grandmother, whom she resembles greatly, is clearly devoted.

Halima works for CMMB. Her salary may be relatively decent, but supporting three children with food and school fees will not leave much, if any excess.

Beyond the Emotional Costs

How much will T1DM cost Kerima and her family? How much does it cost a family to provide the basic level of care and support a patient, to keep them alive on a daily basis, without considering the long term monitoring and surveillance? Coming up with even an approximate figure is problematic, because of a wide disparity in prices even within one country, and the many ancillary costs.

In the US, the estimate is approximately USD$3,000 a month; it is similar in the UK. In both countries, costs are covered by centralized healthcare systems (National Health System/NHS in the UK or private health insurance in the US), though these are not universal systems and many people from poor backgrounds will struggle to meet costs. In addition, insulin prices have increased globally between 2010-2017 by 270 percent, leading to accusations of noncompetitive pricing.

I look at Kerima’s mother, aware that she is struggling. Her head is in her hands, a look into the middle distance that normally means one thing.

“I know this is a lot of information to take on board.”

“It’s hard.”

Harima raises her shawl to her face to wipe her eyes. I can’t offer a tissue as I would in the UK. We don’t keep tissues around because they go missing quickly.

We look at Kerima as she lies in bed. Since she has been in the hospital, I have not heard her speak a word, nor seen a smile.

“Does she talk at home?”

“Yes, a lot. But here she feels very shy.”

I can’t find the language to begin to explain how complicated global pricing of a drug like insulin is.

This is where collated statistics and reality on the ground diverge sharply, as theory and practice often do. Statistics will tell you a that a year’s supply of insulin might cost as little as USD$70 for Kerima. But the disparity between this calculation and actual cost is itself a fascinating and depressing insight.

There are many obstacles standing between Kerima and fairly priced insulin. First, the insulin and necessary equipment, including testing strips, are not produced anywhere in South Sudan. The medicine and supplies that Kerima needs to stay alive are subject to the caprice of border crossings, seizure along insecure routes, and route closure, which means that there is already a cost premium placed by the supply chain.

St. Theresa’s administrator, Sister Laura, relies on a contact in Uganda to order drugs and supplies. But the hospital lacks a fully automated, up-to-date drug inventory system. Paper records frequently fail to alert the hospital to impending drug shortages. We can order supplies, but they can take up to 15 days to arrive by plane. The larger orders can take two to three months overland, with significant risk of seizure by bandits along the roads from Uganda to South Sudan via the Democratic Republic of Congo. Recently, when three diabetic patients arrived at the hospital simultaneously, we ran out of test strips, using up a month’s supply in just two days. In such circumstances, the risk of exploitation increases markedly, as people seek to profit from the desperation of the sick. If only it were as simple as spending a specific sum to achieve a solution.

Kerima’s mother looks at me.

“Is there no other way?”

“Other than injections?”

“Yes. Is there no other medicine?”

I don’t think I should even think about sharing the front line of treatments for T1DM right now. The egotistical desire to offer any hope as a professional seems particularly inappropriate here.

What Next?

Should we rely on technology to solve some of these problems? The decision is complicated. In Kerima’s case, we can either train her family to manage her blood sugar levels, including testing and administering the insulin by hand, or we can outsource an insulin pump, which performs both functions. Our research suggests that an insulin pump might cost USD$1,500 and the insulin approximately USD$400 a year. The pump will not require testing strips, which might otherwise cost USD$1-2 a day.

In either case, there will be many other costs: travelling to and from clinics, cleaning the skin and avoiding infection, and other, almost inevitable crises associated with T1DM. It is not easy to estimate the total financial burden on Kerima and her family, but it will range from USD$1000 a year without the pump, to a first year cost with the pump of approximatley USD$2,000. If—and this is a big if—the insulin pump arrives in good, working order, is maintained, and does not suffer accidental damage or theft, costs will decrease.

But, is this the lowest cost solution available to Halima and Kerima? The average spent on an individual’s health in South Sudan is between USD$28 and USD$70 a year and the average income is USD$1,500. However, these figures conceal massive income disparity. Poverty is endemic in South Sudan, with at least 80 percent of the population defined as income-poor and living on the equivalent of less than US$1 per day.

No matter how you interpret and analyze these macro-economic figures, the picture is stark.

On one side, the cost of managing and treating a ‘Kerima,’ a young girl in a rural setting, off the beaten path, subject to price instability, over the course of a year, will range between USD$600 to over USD$2,000.

On the other side, place a series of statistics.

- How much do most families (>90%) in South Sudan earn a year? Less than USD$400.

- How much is spent privately and publicly by South Sudan? Approximately USD$28-70 per person.

- What funds are available from central and regional government to assist? Practically zero.

The precise numbers can be argued, but every minute spent arguing about the cost of the medical care and treatment to keep a young T1DM patient alive in South Sudan and how that amount exceeds the available resources, is a minute wasted.

The stark reality is that without external assistance, neither option—the insulin pump, nor the simpler, manual approach—is available to all the Kerima’s out there in the developing world.

Kerima’s mother has taken her out of bed and is hugging her gently. The staff nurse who walks by comments softly.

“She only wants her mother.”

I look at them. I know the feeling.

Kerima needs a solution now for next month, then the next month, then the next year. She cannot sit in the hospital indefinitely, waiting for us to develop a system to secure long-term treatment and supplies at a reasonable cost, which her family might not be able to afford anyway. We need to think on our feet and find a short-term solution. Halima needs to return to work. The hospital needs the bed. Kerima wants to go home and back to school.

Yes, I think of the medium and long-term. The issue of life expectancy hovers in my peripheral vision, occasionally winging its way into sight. Life expectancy of young T1DM patients in Sub-Saharan Africa is not heavily researched. A 2006 study suggested that in some parts of Africa, life expectancy of newly diagnosed T1DM was less than a year. Frustratingly, there are few studies carried out or able to be carried out perhaps. A civil war lasting five years, on top of a long struggle for independence, does not lend itself to a great appetite for methodical research.

But we’re not even at the point of thinking about the medium term. All the studies in the world will not keep Kerima alive if we and her family do not safeguard her treatment for the next six months. This is not a theoretical study, as much as one wants to retreat behind statistics and odds. If Kerima does not get insulin today, and every day going forward, she will die. T1DM may be one of the great chronic conditions of the West, but here it is often an acute killer.

I say the words that make most sense to me, as a healthcare worker, regardless of the context.

“The important thing is that you are not alone in this. The solution is not easy but between us, we can make it. If we work together.”

I think of the local services available in the UK, specialist nurses, primary care, secondary care, and follow-up. If any of these services fail, there are a variety of government and non-government bodies that provide formal and informal oversight of the system. The medications and test strips are free for all.

There are two patients waiting to be seen. The first is seriously sick, a complication of HIV. I have to stand up and leave Kerima now. What a luxury to be able to choose when and how to engage with a disease like T1DM.

I clerk in the patients and I forget about Kerima in that moment. An easy solution to the personal anxiety and conflict she instills within me.

No Easy Solutions

The one abundant lesson to be learned quickly in medicine in the developing world is that there are no easy solutions.

Do we rely more heavily on technology in the case of Kerima or keep it simple?

How far do we trust the family to deliver the solution we have worked out? How much do we involve the family in these decisions? Patient choice and education seems a slightly trickier concept in a country ravaged by conflict, corruption, low employment, and low trust.

Later that week, I happen to hear Kerima receiving the first dose of insulin before she goes home. Rather than the intravenous insulin, she will now begin to be injected into her soft tissue.

The cries ring out through the ward, disturbing our ward round. The nurse who has delivered the injection is struggling to keep Kerima still. The mother is getting agitated. It takes two minutes and sounds like torture.

This will happen twice a day for the rest of her life.

Above all, one question lingers in my mind…

Even if we can be sure that spending the money on Kerima will give her 10 or 20 or more years, can we justify it when that money would, in the short term, pay for three local healthcare workers who might otherwise leave the hospital and seek employment elsewhere?

And given that this money does not guarantee anything but simply gives her a chance, do we spend it? How do you quantify a human life in this setting? Is the money better spent on five extra years of life for Kerima or the salaries of several staff nurses on the ward for the same period?

This is where I struggle.

I don’t have an answer. If we were dealing with a faulty car requiring an indefinite expenditure that would not guarantee much, the decision would be easy. But Kerima’s story forces us to ask: what is the value of a human life regardless of efficiency, outcome, and utility? When do we throw a precious life belt,? When do we pull one person out of the water when all around us are struggling?

Perhaps one day, if we invest in Halima and Kerima, they will become local experts who can assist others. Halima can keep working for the American charity. A small but important brick can be laid in the community, laid by hands that cared for generations to come.

Islands of stability and hope. St. Theresa Hospital. Kerima, and Halima too? All we can do as individuals is start with individuals. Invest in them, and invest in each other.

I watch Kerima and Halima going for walks in the hospital, holding hands. I hear her crying because she is no longer allowed to eat whatever she wants. How to explain to a six year old that she is different now than her school friends, different in diet, different in body.

I have told this mother and daughter they are not alone. I say we will work together. I say that we will find a solution together. But I didn’t just mean the hospital or CMMB. I meant the global health community. We should be there for Halima and Kerima, holding their hands along the way.

I want to take responsibility, to guarantee that I will be there for the family. But will I be in South Sudan in a year’s time? Who will look after Kerima once I am gone? Am I providing false hope? Is it a salve to my conscience?

If we are not there—with Kerima—can we really talk about global health?