Meet Sebastian: A Champion Whose Changing Lives

Erica Tafadzwa is a public health professional currently volunteering with our team in Zambia. She dedicates much of her time serving the members of our CHAMPS (Children and Mothers’ Partnerships) community in Mwandi. The goal: to make the most vulnerable families healthy.

To help achieve this goal, Erica serves side-by-side with our inspiring and committed community health workers. She is so inspired by these dedicated and hardworking Zambians – members of the very communities that they serve – that she decided to share one story to help shine a light on how their commitment improves lives.

Meet Sebastian

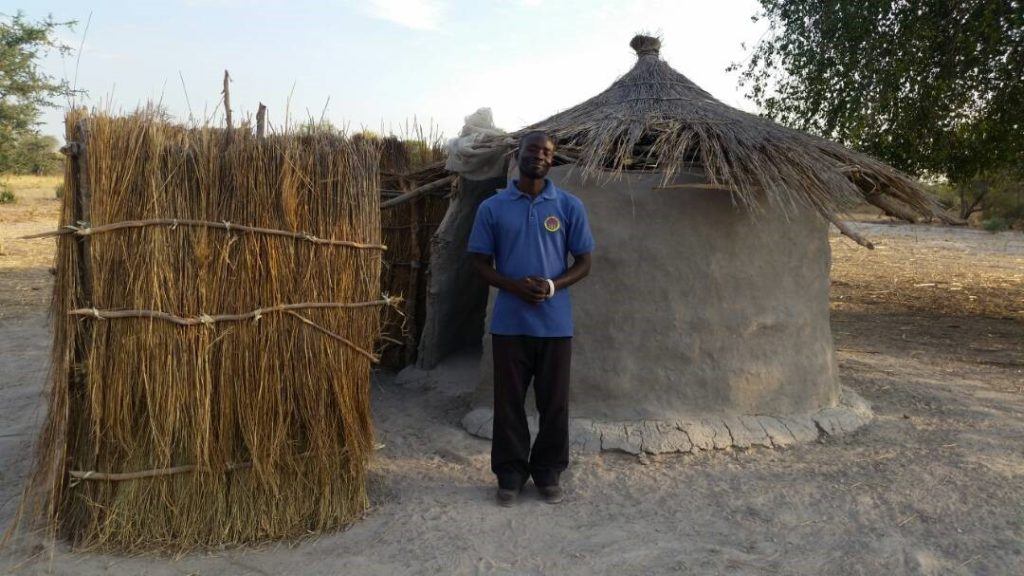

Meet Sebastian Sibungo. He serves as a CMMB water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH) Champion in his community and communities around him.

Sebastian Sibungo, aged 41 was born into a family of seven. He has four children and also cares for many nieces and nephews.

Born and bred in Livingstone, Sebastian attended school from 1983 to 1995, and completed grade 12. From grade 9 to grade 12, Sebastian began to experience vision problems which negatively impacted his educational performance. He worried about his future.

In 1996, Sebastian began working in the catering departments of hotels including Faremont hotel, Chrisma hotel, and SUN Hotel Zambia. From there, he transitioned to a cleaning Job at ZANACO. He did whatever was necessary to earn money to take care of his family. In 2004, his parents decided to leave Livingstone and return to their original home in Mwandi. Shortly after returning to their home village, Sebastian’s family experienced many challenges. The most devastating was his father’s loss of vision, which made an already challenging life more difficult. In addition to learning to navigate life without sight, Sebastian’s father also had to deal with theft. People stole his father’s livestock (cattle and goats).

Looking at his parents’ situation, Sebastian made the decision to move to the Mwandi. It was a difficult transition for Sebastian, his wife and children. They had spent all their lives in the city. Mwandi is a small Zambian village with a single tarmac road. The district is a very poor, rural area. Most people live in mud huts. The community is challenged by a lack of safe water and access to healthcare.

Living in Mwandi

It took his family years to adapt to village life, it was not easy. In order to fend for his family, Sebastian began a mobile store where he sold medicines for livestock, seeds, and children’s clothes. Unfortunately, this did not last long, as the community members were not supportive of his business.

Sebastian then moved into the business of buying and selling animals. However, this required him to spend days away from his family and they just could not cope without him. In the end, he decided to stay at home and shepherd his animals. Life was difficult.

However, as time passed, they settled in their new home and life. Sebastian remembers the day when the Induna (village head) called a meeting asking for those willing to work to improve their community without payment. It was here that he first learned about CMMB. He was excited about the planned programs to improve the lives of the most vulnerable through community-based initiatives. Sebastian prayed that he would be one of the people chosen to join CMMB.

I have the honor of working with Sebastian, and witnessing his amazing commitment to his community. I recently sat down with him to learn more about what motivates him.

What motivated you to become a community volunteer?

I have a heart to help the people in Mwandi. But I need enough knowledge to be able to do this. CMMB equips us with knowledge that can transform lives. After being trained on Community-Led Total Sanitation (CLTS), I realized that many of us in the community engaged in unhealthy behaviors and practices. I never had a toilet before. Now l have a toilet and I have encouraged others to build their own toilets too.

2.4 billion people still use unimproved sanitation facilities, of whom 1 billion practice open defecation (OD). Nine out of 10 people defecating in the open live in rural areas (WHO/UNICEF, 2015)

Tell us about the CLTS training with CMMB.

I was trained in March of 2017 by Janet Choongo, a CMMB volunteer. This training opened my eyes. l learned that the practices of people in our community were very different from what we were being taught to do. What was normal to us was not normal or healthy, and I realized that we were in danger.

Community Led Total Sanitation (CLTS) is an innovative methodology for mobilising communities to completely eliminate open defecation (OD). Communities are facilitated to conduct their own appraisal and analysis of open defecation (OD) and take their own action to become ODF (open defecation free). At the heart of CLTS lies the recognition that merely providing toilets does not guarantee their use, nor result in improved sanitation and hygiene.

For most people in our villages, answering the call of nature in the bush was a common practice. It was just what people did. Too few people understand the dangerous implications of this behavior.

The training also highlighted the importance of hand washing, something I took for granted, and which most people still do. Learning that unwashed hands can lead to the passing of germs was news for me. Especially, through handshaking, a common practice amongst the Lozi people here in Mwandi.

Handshaking spreads cholera germs. So, it is important to wash hands frequently and properly with soap. After the training, l was motivated to work in my community. Most villages had no latrines, even fewer had hand washing stations. In some villages, I teamed up with my colleagues and triggered the community members to act. When I say ‘triggered’ what I mean is talking to people about open defecation in a way that really demonstrates how bad the practice is. It brings out factors such fear, disgust, and shame. It is not an easy process, but we do it with respect and love. We do it with a common goal of improving the lives of our brothers and sisters.

How did you get access to the communities?

We always started by talking with the Indunas, the community leaders. went to talk to the leaders. We informed them of our intended work, to make the villages open defecation free. Together with the Induna, we agreed on dates when we could meet their community members. Gaining the trust of the community is key. This is not an easy subject. People don’t want to be told that their longstanding practices and behaviors are wrong and dangerous.

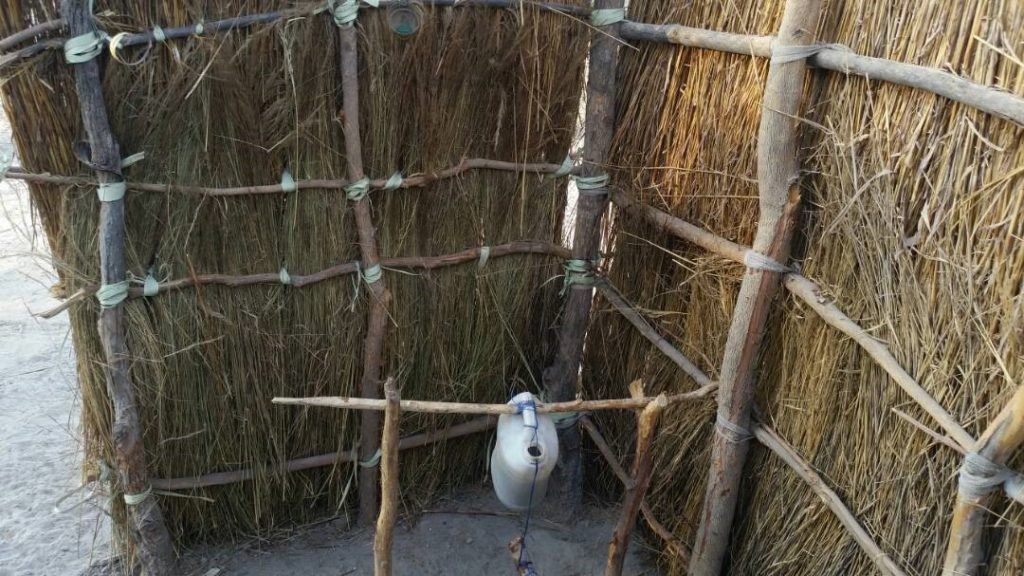

In addition to helping people see how behavior impacts health and well being, I also make sure to let them know how easy and cheap it is to build a pit latrine using locally available materials. I have learned that in order for your voice to be heard, you have to lead by example. Therefore, l started by building my own toilet which I invite people to come and see.

What are the challenges that you have encountered in your work as a Community WASH Champion?

When l began the work, l realized that people’s beliefs interfered with their health. It also often stopped them from taking action.

Some believe that a pit latrine toilet will be a house for snakes and other animals. A totally realistic worry. So we help people understand that one of the requirements for a fully adequate toilet is the lid to cover the hole. This prevents flies and other animals from going into the hole (and therefore prevents flies and animals from contaminating food or water sources in and around people’s homes.

Another challenge is the movement of people. For example, during fishing season, people move their families closer to rivers. What you’ll find is that someone who was triggered to build a latrine then moves away and never uses it and they rarely set up a new one in their temporary place by the river. This of course means returning to old practices that increase risks for all those in the area. Even if just one person doesn’t use a pit latrine, the health of all those in the area is at risk.

How has having a pit latrine impacted your life and the lives of those around you?

I built a toilet for my family and a hand-washing facility with soap, including a lid to cover the hole and took some other measures to scare away the snakes!

My family no longer goes into the bush. Ever since the CLTS training and ever since l built the pit latrine toilet, we have practiced better hygiene and sanitation. We have not had any diarrheal illnesses since!

The community members are very supportive of our work and they have come to see the value, convenience, and dignity that comes with having a pit latrine toilet. Our communities encourage us to continue with our work.

I have perhaps been most proud of how my children also talk to their friends in school about the importance of using toilets, washing hands, and other good hygiene practices. I wish I had known earlier.

Tell us about your own village, what is the progress?

When we were being trained on CLTS, one of the things the trainers emphasized was that we should start the work in our own villages. Each champion should have a toilet and then ensure that the members in their own villages are triggered to build toilets and use them.

My village is called Sishekano village. We have a total of six households, but only four had toilets. Remember even one person changes everything. After the training, l went on to trigger my neighbors, who all now have fully adequate toilets. We are waiting on being certified as an “Open Defectation Free” village which will happen soon. All the households in my village are happy and encourage me to do more work that will help to improve their lives.

What are you future plans as a community volunteer?

With full support from CMMB, l can go beyond my catchment area to ensure more people learn what I have learned. I even want to keep working with dedicated champions in my area and trigger schools and churches. I would also like to be trained in other areas so that l can continue to improve the lives in my own home and of course my community

You change one individual, you save many lives’