A Conversation With Dr. Tom Catena

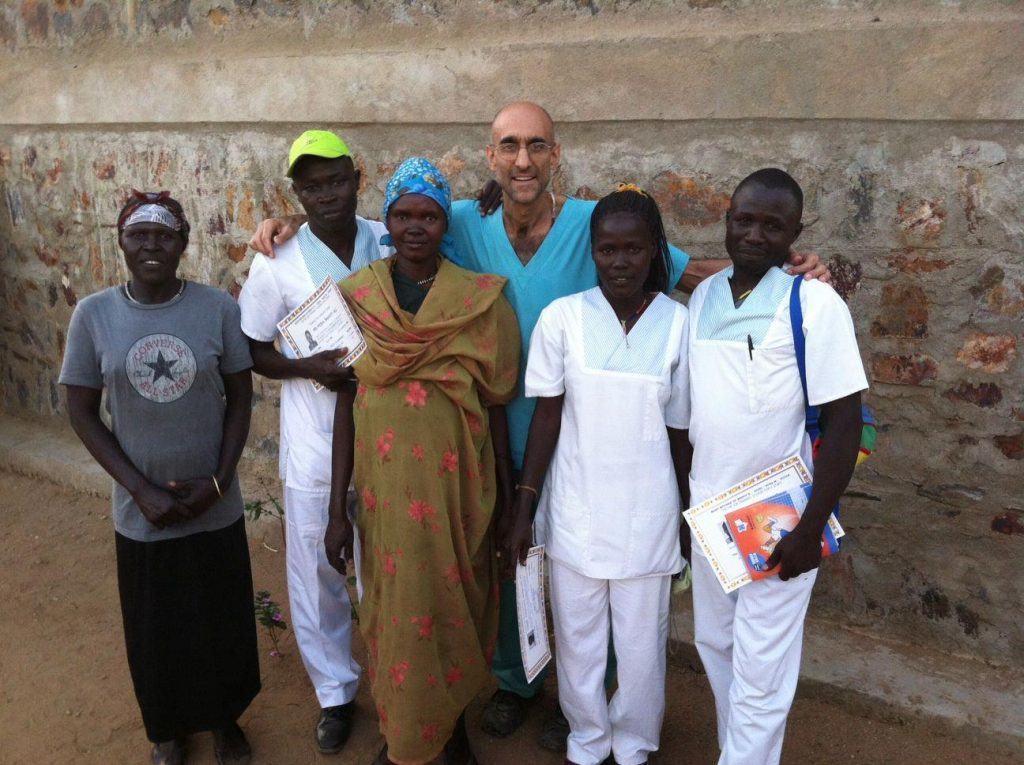

Longtime CMMB volunteer and humanitarian, Dr. Tom Catena is a finalist for the second year in a row for the prestigious Aurora Prize for Awakening Humanity. He has been serving the people of Sudan’s warn-torn, Nuba Mountains since 2008. He typically treats up to 500 patients in a day and is on call 24 hours a day, seven days a week, delivering babies, performing surgeries, and treating injuries resulting from bombings. He has saved the lives of over 1,700 victims of war and countless others.

We recently had the honor of speaking with Dr. Tom via Skype from the Mother of Mercy Hospital in Sudan, about his courageous work and being a finalist for the Aurora Prize.

Congratulations! How does it feel to be a finalist–again–for the Aurora Prize?

Thank you. It’s a bit intimidating and to be honest with you, I am just kind of here, taking care of some people, and I am just filling a small cocoon. But awards serve their purpose. If it helps tell the world about the atrocities happening in Nuba, and the amazing work of the church and the people here, then I feel blessed to be a finalist.

You recently were married. How has becoming a husband changed your life?

My wife, Nasima, is a nurse here at the hospital. We first hired her seven years ago. She did her nursing school in South Sudan. Nasima was first one of the ward nurses, and now she’s in charge of one of the wards. She is from this local area. Nasima and I became friends before she went off to school and we kept in touch while she was there. When she came back home, we decided to make something permanent.

When Nasima first met me, she said she was terrified. I mean, she was brand new and I was teaching her a few things. So, I told her to bring me gauze, a patient had a wound or something, and she was so afraid she was shaking. She dropped the gauze and I think I started laughing, and she sort of got over it. I think, maybe she was able to see kindness in me. I am just using a word Nasima used. She found a certain kindness in me that I think she didn’t expect.

Now, I can say that being married is a huge plus, a big benefit. I, of course, waited until late in life to do this, and I don’t think I ever thought it would happen, but it’s been a huge benefit and a really great change in my life. Before it was all work, work, work, and there wasn’t anybody to share the ups and downs with. So, it’s so nice to have somebody around to share with.

It’s kind of strange, because people always talk about marriage being this big adjustment, and so I am waiting for this big adjustment to take place. I haven’t seen any problems. I mean obviously, I have never been married before, never been with anybody, so I have nothing to compare married life to, but I don’t see any downside to it. A tiny bit of respect, a tiny bit of love, and a tiny bit of kindness, and it’s been quite easy.

Of course, Nasima is a very easy person to love, and so that might have a lot to do with it. But I am still waiting for this big adjustment–this change that everybody talks about. There haven’t been difficulties that everybody talks about, but I don’t know, maybe they come in the future. We pray every day to God to keep us strong, and keep us loving each other, and we think this is helpful. We attend daily mass together. We make it over there at about 6 o’clock in the morning; that is a big help for a relationship.

Tell us a treasured memory from your childhood.

I remember Friday nights when the school week was over, the family sitting around eating dinner. Every Friday night, my mother made a couple of pizzas, and we always had either lentils or some kind of pasta, some great food, and we would all sit, and eat, and talk, and just relax. It was a very calm and peaceful environment. That’s what I remember, just sort of good food to celebrate the week. That’s just one of many good memories off the top of my head. I am dying for some of my mom’s pizza right now!

Why do you what you do? What keeps you giving?

There was a reason I was born with so many positives, so many blessings. And I think it would be rather selfish to kind of take all that I was given from birth onwards, and use that all for myself. There is some payback for me in this life. Not that I am suffering by any means now, but I think that giving something back is part of what we are expected to do.

What’s it like for your family to have you so far away?

I think that my parents do fear for my safety. They never let on about it. I think they try to separate that from what they tell me. I think my parents and my family also have a lot of faith. Whatever comes is the will of God, and they are not to interfere with that. They see this as my calling and my place in life, and I think all of them respect that. They would never feel that it’s their place to interfere, to say, “You know, Tom, you need to come home. That place is not safe.”

I really appreciate that my family, my brothers and my sister, my parents, my aunts and uncles, are always really supportive, because I think they do really have that fear for my safety. Despite that, there has never been any pressure at all from them to come home and be back with them to get away from the danger. They have been extremely supportive and I really appreciate that. It would make things difficult for me here if I felt like my family was not happy.

You once said that when you were studying medicine, that children scared you. How’s that changed? What do you learn from them?

You can be in the worst mood, and have so many things in your head, and you see one kid that is improving, or one kid that wants to joke around with you, and that can change everything in an instant. To have some kind of a balance like that, to see at least some children–to see the ones who are getting better–that brings a little bit of levity to the day and it’s a huge benefit. Otherwise things can be pretty dreary. It can be quite demoralizing if you don’t have that little sort of pick me up sometime during the course of the day. For me, it’s really essential to have that mix, and I really appreciate seeing kids.

Even the kids who were badly wounded in the fighting, children who were amputated, once they get over the acute injury and the pain kind of goes away, they really just want to play, to joke around and goof around a bit, and they seem to have forgotten all the trauma. It’s amazing. I mean, who knows long term, hopefully that will stay forgotten, but they are incredibly resilient and very tough.

Can you share a story that has stuck with you?

As children can bring incredible joy, they can also bring immense grief; grief like you’ve never felt. One child that comes to mind is a boy named Chalu, who was about 11 years old. He was hit by an incendiary bomb from the antonov, and the bomb exploded with a blaze of fire and he was burned over 60 percent of his body. These were full thickness burns, so the whole skin was burned through, and he was on the ward for months.

He survived for probably three or four months on the ward, and every day we would go and see him. Every single day. We’d look after him and talk to him. The nurses of course did most of the work, changing dressings, they really had to bear the brunt of his suffering, but to see that kid every single day, and watch him suffer, that was difficult and taught me a lot.

Chalu eventually died from his wounds. I think that these kinds of experiences never quite leave you. All you can do, when these things happen, is try to file them away. You try to force yourself to forget it, and move ahead. You try to keep going because there is always somebody else in line that needs your help. For your sanity and peace, you need to forget these terrible experiences, and try to move ahead.

Sometimes you have to take risks for the benefit of your patients. How does it feel to push the limits of your training?

I would say it’s terrifying to do that, and it’s a very uncomfortable feeling. There are times in my situation here when I may be performing an operation that I am not fully comfortable doing, knowing that there is no other option. I’ve got to make sure I weigh potentially causing more benefit than harm. If I think the potential for benefit is there, I’ll do it. It’s a very uncomfortable feeling. It’s also very humbling because we are reaching the end of our knowledge, and we have to acknowledge that we have limitations. I think it’s just trusting ourselves to God in this case, and saying, “Look– we are really trying our best and I think if we do nothing the outcome will be worse than if we try something.” It is still a very uncomfortable and very terrifying feeling, and not something I enjoy doing, but sometimes you have to bite the bullet. You have to just do it, just go ahead, and push through. If someone can benefit and you can help, you have to try.

This image of Dr. Tom in surgery is from the documentary “The Heart of Nuba,” produced and directed by Kenneth Carlson.

What are the biggest needs at the Mother of Mercy Hospital right now?

We always have problems with structural maintenance. We have some local Nuba people who are very good and they’ve fixed some of the buildings. However, having someone permanent who can maintain our solar power, water supply, and the many physical plant problems that we have is certainly one area that is lacking. It’s difficult. We are still struggling a bit in our laboratory. We have people in training now, but the rest of our staff here are trained on-the-job. Having a skilled laboratory person that can really supervise our on-the-job trained people would be a big help.

Do you ever lose hope or want to walk away from it all?

That happens about once a week (laughs), when you just say, “Look, I think I’m maxed out.” You kind of have your little tizzy fit, if you want to call it that, and you come back to your senses and say, “No, wait a minute, that’s just how it is, that’s life.” I think, that I, along with other missionaries here, and the sisters and the priests, I think we are called to this work. We made a commitment. We haven’t taken a vow to the Nuban people, but we’ve made a promise to ourselves. We made a commitment to do what we can to help the people here, in good times and bad. In a sense, it’s like a marriage vow.

Those episodes, those instances, come up all the time. The frustrations can be overwhelming. You kind of have your moments when you say, “I’ve had enough.” You get annoyed for awhile, and then you come back to your senses. And I am always brought back by the thought that I made a commitment. Am I going to stick to that? Or am I going to back out? Am I going to give up, and take off from the people here? Something with the Holy Spirit and the grace of God draws me back to keep up with the fight. I think that as long as I am operating within the grace of God, that will stay with me. I hope and pray that I don’t wander off from that.

What words of advice do you have for people considering volunteering?

First, it’s best to not look at me as some kind of “super doc” because I’m not. I’m just a normal doctor. I am a family practitioner by training. Most of the surgery I’ve performed, I learned on the job. I had some great people when I was out in Kenya, that took a lot of time with me, really experienced surgeons who taught me a lot of techniques. So, whoever you are, and whatever level you’re at, you have a lot to offer.

Don’t look at somebody else and say, “That guy really knows a lot of stuff and I can’t approach him.” That’s not the case. Just try it. Make the effort. Try to learn what you can about the place you’re going and just make the effort. If you catch the volunteer bug, like I did thanks to CMMB many years ago, and you want to stick with it, fine, you stick with it. You keep learning. You see areas where you can contribute. You know, I think if nothing else, in a lot of these places, just seeing somebody from another country who says, “Yeah, I’m coming here to help you guys. I care enough about you to come here, and show up in your country.”

That says a lot to the people there–the fact that you’re showing up. We should keep that in mind. We approach it in a humble way, approaching it in a way that there is a lot we don’t know about the places we go to. You just say, “Look, I am here and I am with you guys. How can I help you?” There is a lot people can offer. You don’t have to know everything. You go with what you know, be open and willing to learn, and you can contribute a lot.

What do you want people to know about the people of Nuba and their situation?

This is a people who have been put down, oppressed, and erased for so many centuries. My hope is that they have some degree of self-determination or autonomy, where they can select their future and chart their own path, for better or for worse. I know we had the example of the course of South Sudan, and we pray vehemently that the course doesn’t go that way, but I just hope that the Nuba can be given their sense of identity, sense of autonomy, and sense of self-determination so they can forge a path for the future without too much interference from the outside.

I hope they can feel a sense of pride, a sense that they are doing things for themselves. They’re very independent people, they want to do their own things and I really hope they can be given that chance. They can feel it for their own people that they belong to themselves, that they’re not under anybody else’s thumb. That’s really what I hope and pray for.

What’s the best advice you’ve ever received?

The common advice is follow your passions, which is kind of a generic thing, and I can’t think of any one person who told me that, but thinking through what I wanted to do with my life once I finished college, that idea kept coming up. Different people were saying it, “Follow what is in your heart.” So, instead of just following what you think other people think you should do, follow what’s in your heart. I think everybody has something that’s deep in their heart that they really want to pursue, and it’s very easy to be displaced from that path by so many other competing factors. Your family is telling you to do something. Your friends are telling you to do something. Society is telling you something else. And I think, in the end, if you just follow what you feel, and it is a feeling, follow what’s deep in your heart and pursue that. Sometimes you don’t know where it’s leading, but just follow it and the path will become clear to you. Follow what is inside your heart. I think every single person who will end up not following it, got thrown off the path for one reason or another. There are a lot of practical reasons. I had many. I had the luxury of an understanding family, a good upbringing, financial security, all these things; there were so many things that were going in my favor. I really consider it a luxury, another gift and grace from God that allowed me to follow this path.

You inspire so many people around the world. Who has inspired you?

Saint Francis of Assisi has been my personal, favorite saint for many years, as he is for half the world, Christians and non-Christians alike.

Growing up when I did, in the 70s, 80s, and 90s, Mother Teresa of Calcutta was a huge inspiration to my entire generation. We always had this idea that saints were people who lived 500 years ago, they were out of touch, and that they were people who were above everybody else. But here was somebody, a sort of very quiet, humble person, who was living in our day and age. She was doing very simple things, but at the same time, very incredible things, and she was a tremendous inspiration for me, as she was for so many other people. I think it was so important to have somebody, a contemporary person, a Catholic person, in modern day, who was living the Gospel life that we could relate to very well.

Show Dr. Tom Catena Your Support

Support an International Volunteer