How a Tiny Baby Delivered a Lifesaving Reminder to our International Volunteer

Sarah Rubino is a nurse-midwife serving at St. Therese Hospital in South Sudan. Over the past eight months, Sarah has shared several stories about her experience volunteering. Some are stories of joy and others loss. In this story, Sarah gets a very important reminder by one of her littlest patients.

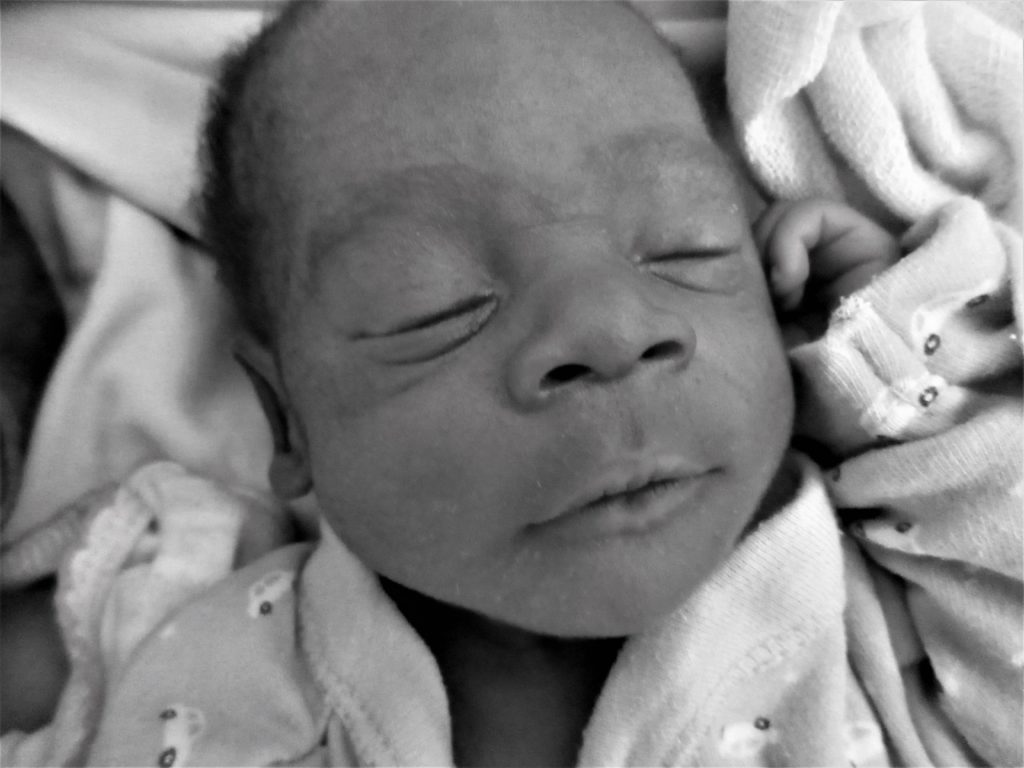

The Innocent Gaze of a Child

It was a Saturday morning as I made my way to the maternity ward. Once again, a downpour of rain had turned the dirt roads into paths of mud. As I entered the doors of the ward and proceeded to stomp off the muck, the community midwife who was finishing her night shift ran up and started telling me about a baby who had been born prematurely that night.

All I heard, as I headed over to the beds, was that the baby desperately needed oxygen but there was a shortage of power. With the hospital’s only source of electricity coming from solar panels, the cloudy weather from the day before limited the amount of power stored up for the evening. Most days we are able to get through the night without trouble, but when the next morning brings more clouds, the used-up batteries are unable to recharge. Working without light isn’t as big of a problem. But, working without oxygen when someone needs lead to tragedy.

The mother was sitting next to a bed with a small lump under the covers. Nervously, I pulled them back. I can’t count how many times I have done this exact same thing, only to find a lifeless baby, and having to then tell the mother that her child had died.

But this time was different. I breathed a sigh of relief when I saw a tiny healthy body wriggling around.

She had to be less than three-and-a-half pounds, but from her skin color and her vigorous cry, I could tell that she didn’t need oxygen. Without using words, the anxious mother pointed forcefully to the lump on the bed again and I quickly understood what she was trying to say. As I peeled the covers back further, I realized she had delivered twins.

Next to the vigorous baby girl lay an even smaller baby that, to my dismay, had a grey color to his skin. I could now hear his weak breathing as the sacs in his lungs collapsed after every breath. He was minutes from death.

I grasped his almost lifeless body and ran over to the resuscitation table. I grabbed the Ambu bag with the tiniest mask I could find and immediately started breathing for him. Being in this remote area, we have little to help resuscitate babies. Using the simple bag and mask, I was able to use positive pressure ventilation to help keep the alveoli sacs in his lungs open.

By now, the sun had been out for a little while, enough for me to start up the oxygen machine for a short time. His color slowly started to come back as I continued to breathe for him, but I could hear the beeping of the solar batteries menacing that the power was about to run out again. I felt a sense of dread creeping in as I continued to breathe for him.

Regardless of the power, I could see that what I was doing wasn’t enough and that it was probably too late for him to recover.

A chance to breathe

I continued to breath for him as the commotion around me increased. Even though this little boy was unlikely to survive the hour, his twin sister had enough fight in her. We decided that sending the family to Yambio State Hospital – where an incubator and oxygen was available -it might be the chance she needed to survive. The midwife was able to get a hold of the ambulance driver, and just as the power went out and the oxygen machine stopped, the ambulance arrived.

The ambulance was cramped, with only enough room for a small stretcher and bench in the bed of the vehicle. The ambulance had no medical supplies inside and no oxygen machine. Even though the ambulance is very minimal, it’s able to get patients over treacherous dirt roads to a medical facility.

Often, it is the only way to get to a medical center or hospital, besides walking or where possible, riding on the back of a motorcycle. It was decided that despite the muddy roads, and the condition of the baby boy, the twins’ survival hinged on getting to Yambio State Hospital before the next storm hit.

I continued to breathe for the baby boy as I got into the front cab. The mother clutched her tiny baby girl while she and her husband climbed into the back of the ambulance. It was a surreal experience for me as the driver sped off as fast as was safe. And as he rushed us to the hospital, I sat there holding this tiny human in my lap, one hand gripped around the mask and his head to form a tight seal, as my other continued to pump breaths for him. I was the only medical person present in the vehicle. I was the only person that could keep him alive during this hour-long journey.

Shortly into the drive, evidence of the morning’s downpour became more evident as we navigated sections of washed out roads and lurched into potholes as deep as my passenger window. During those rough and jarring moments, I had to stop breathing for the baby boy and clasped him close to me, fearing he would bounce right out of my hands. I was numb and emotionless up to this point as I tried to focus my mind away from the nausea growing in my stomach.

I could tell that my mind was spent and my nerves were shot. All I kept thinking was, “this little baby boy is going to die in my arms in the middle of the thick bush of South Sudan.” Too many times had I held a tiny lifeless baby in my arms. Too many times knowing I had the knowledge to save these premature babies, but not the medical equipment to do so. Too many times had I wrapped these tiny, little bodies up in a shroud as mothers sat sobbing next to me.

Then he looked at me

His dark newborn eyes peered over the breathing mask and fixed on my face. It was such a simple thing, but that look instantly snapped me out of the cold place I had slipped into. No matter the situation, the pain I was in, or the possibility of his imminent death, he was alive at that moment, and I had that moment to cherish his short life.

I went from taking care of him to caring for him. The medical care I was physically administering didn’t change, but now, I was cradling him with love and appreciation; appreciation that he was in my life, no matter how short the moment might be. I had let compassion fatigue build up until I was burnt out, but this tiny baby’s gaze pulled me out of it.

We’re finally there

We finally made it to the hospital and I rushed out among a throng of people. Hundreds were milling around the outside of the hospital. Families stood around in groups waiting to hear about their loved ones after a grenade went off at a dance club the night before, wounding at least 50 people.

I stood out like a sore thumb as I forced my way through the crowd. Soon a clear path started to form as people noticed the tiny body in my arms. I was still keeping him alive with a bag and a mask. I was led into a small room crammed with four hospital beds, ten mothers with their babies, and an incubator.

A large oxygen machine was brought in five minutes later, and the baby boy was finally able to be hooked back up to oxygen. I laid his sister next to him to keep him warm and struggled to say goodbye. I knew his chances were slim, but that he had a better chance at surviving here then with me. Then, I had to do the hardest thing – walk away. Letting go after realizing you have done your part is heartbreaking. I had given this baby my everything, but knew I had to hand him over to the care of others.

A month later, I just finished rounds on the pediatric ward as a nurse handed a medical document from Yambio State Hospital and said that a father had come to see me with his child. I looked down at the notes and became confused at the words in bold at the top of the page that read, “Child to be reviewed by midwife Sarah.”

Before I could continue to read the rest of the document, the father walked in holding a tiny baby girl in his arms. He started to speak to me in Zande as his wife joined him, holding another tiny baby. My breath caught in my throat as I looked at the baby boy in her arms. These were the twins from a month before! The parents laughed with joy as I shouted in happiness, “Your baby boy survived!”

They were discharged from Yambio State Hospital a week prior and had come for a baby wellness checkup. I held back tears as I examined the twins, and could scarcely get over the shock of it all. Both babies, although small, were healthy. Many premature babies in South Sudan do not have this happy ending, but the story of these twins is one of hope. It also teaches an important lesson.

As a caregiver, whether it be working in the medical field or caring for a loved one, it is important to watch out for the telltale signs of compassion fatigue. As a medical volunteer, working in one of the poorest countries in the world, I have experienced first-hand how exhausting and taxing caring for others is on oneself.

I have always loved caring for individuals who were near life’s end, just as much as I love delivering babies. Both situations, although at either end of life’s spectrum, are vastly similar. There is always a sense of nervous anticipation of the unknown, but when it is all said and done, it is such a privilege to be there at someone’s first breath – or their last.

As a nurse-midwife working in the village of Nzara, South Sudan, I have found myself at both ends of life. When it comes to premature babies, sometimes I had the honor to be present at a little life’s first breath and sometimes at the last. However, these experiences are taxing, and compassion fatigue can quickly sneak in.

After that tough day, I realized I needed to take the rest of the day off and take it easy for the next several days. I was burnt out and knew that taking on too much suffering can make one numb. I had to take care of myself so that I could continue to take care of others, and I had to let go of the guilt that I had somehow not done enough for all the children who had died.

We have few supplies in Nzara, and it gets frustrating only being able to perform simple interventions, while unable to forget the advanced medical technology available back home. However, these limitations must not make us downcast or dejected. As Mother Teresa once said, “Not all of us can do great things. But we can do small things with great love.”