Serving Abroad at the Start of COVID-19: An Interview With Dr. Mike Pendleton

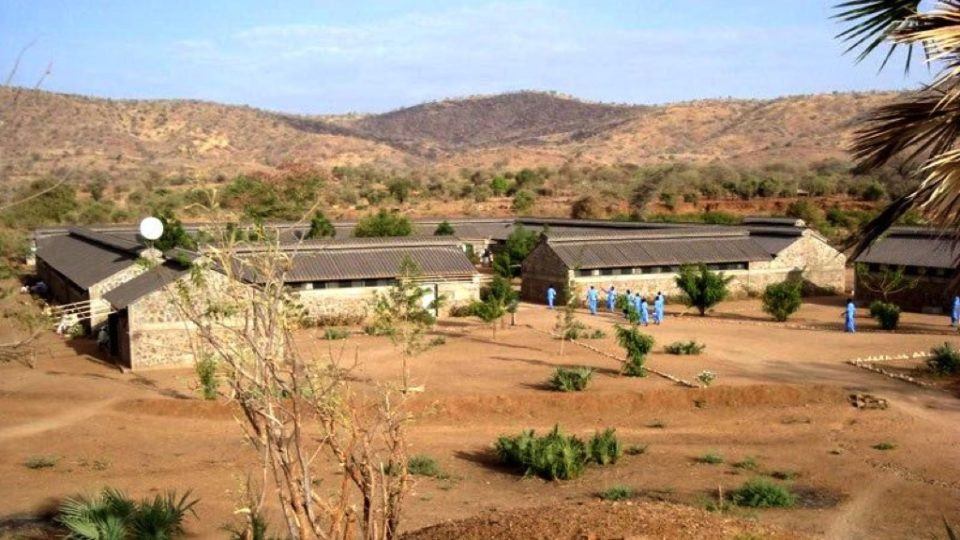

Since the early ’90s, Dr. Mike Pendleton has been committed to providing relief work around the world. He recently returned home from a three-month volunteer experience in Gidel, Sudan—home to the Nuba Mountains and Dr. Tom Catena’s Mother of Mercy Hospital.

In the interview below, Dr. Pendleton shares what it was like serving amid the COVID-19 crisis, the challenges he faced, and the moments that moved him.

You left for Sudan prior to the outbreak of COVID-19. How did the pandemic impact your experience when you first arrived?

I left for Sudan on March 3rd and two weeks later, the world turned upside down. Everything shut down in the U.S., and all of the sudden there was discussion about this particular virus invading virtually every place in the world. So, we got real aggressive in Gidel, trying to figure out how we were going to respond.

People talk about how Gidel is way off in the middle of nowhere, and it’s true, you’re at the end of the road. But because of its remoteness, and the fact that everything is outdoors, I was probably in the lowest risk area that I could be at the time.

Dr. Mike Pendleton (center, right) with other volunteers during an orientation at CMMB headquarters in New York in February 2020.

I had the option to turn around and go home, but I felt that I was where I was supposed to be. I was able to do what I thought was good work and meet some pretty amazing colleagues. By the time I left, there were no COVID-19 cases in Gidel, but we didn’t have testing so it was hard to know for sure.

Did the Mother of Mercy Hospital have the capacity to respond to a potential outbreak of COVID-19?

The only tool we had, of course, was isolation. Early on, that didn’t really differ from the tools at the disposal of everyone else. We had oxygen concentrators but we had no ventilators, masks or additional PPE. One couple volunteering at the same time, designed masks and hired someone to make them on a treadle-powered sewing machine. That was basically our PPE.

What other COVID-19 prevention measures were taken at the hospital?

If the virus did show up in Gidel, the idea was to confine it. We built two large isolation tents and Nadia, the same woman who helped design the masks, educated the nurses and clinical officers about COVID-19. She had everybody trained and distributed masks. We were able to get a hold of a forehead thermometer and started screening people before they were admitted.

If someone had a fever, profound fatigue, and a cough, they were asked to go home and quarantine. But in many cases, home was two or three days away. In those situations, patients were evaluated and put in an isolation tent outside the hospital.

A major concern was that the hospital itself is one of the few indoor areas in the region, other than schools. Because of that, it actually poses the biggest threat for COVID-19. For example, if you are an inpatient in the hospital, and somebody with the virus is laying two beds over from you, there’s a high probability that you get it. So the isolation tents were how we chose to handle the situation in the early days.

How did your patients react to the threat of contracting the virus?

In impoverished regions like Gidel, people are already living with a degree of risk. People die prematurely from things like, malaria, pneumonia, and gastrointestinal diseases. From what I observed, the pandemic didn’t seem to add another layer of risk from their perspective. I mean, these folks have lived through civil war, and they’ve been bombed and shot at.

People in Sudan live in the moment because they have no other choice. A mother, who fears getting the virus after going to the market, is still going to go because that’s her only means of providing food for her family. For her, there is no choice.

Can you tell us about your role at the hospital?

I was responsible for the male ward—the hospital’s biggest ward—and the outpatient department. I approached both as teaching forums. I got to know the nurses and the clinical officers, but the fun part about it was that the nurses were empowered to question my judgment. They talked about their own ideas and the process became very collaborative, which I thought was wonderful. In addition to managing those departments, I mentored the clinical officers during daily rounds. Once a week we’d set aside time for training sessions based on the deficiencies I saw.

Then, when it came to the hospital’s more complicated cases, I’d work with Dr. Tom. It took me a while to catch up with the medicine available in such an under resourced area. In Gidel, diagnosis and treatment is intuitive, with very little lab or imaging.

This isn’t your first time volunteering abroad. What stands out about this experience in particular?

I should emphasize that the Mother of Mercy Hospital has numerous satellite clinics. The hospital identifies and sponsors qualified individuals to go abroad, gain a degree or certification, then return to work in the Mother of Mercy system. The hospital is a really important resource in that part of the world and it’s not just there to treat. If you were to take the Mother of Mercy Hospital out of Gidel, you’d be missing the surgical interventions, which do make a huge difference because they have a lasting effect.

But because of the teaching and training, standard medical treatment would go on. Immunizations would continue and healthcare workers would keep up their outreach. Having those resources in place makes the hospital’s work really unique.

What were the major challenges you faced?

If you look at the Mother of Mercy Hospital, it was designed to have four separate wards. It has very quickly started to bulge out at the seams. Now they have beds outside the wards and in the hallway because there just isn’t enough space. It’s clearly a referral hospital, but it’s also just the local place for people to access healthcare.

Dr. Tom Catena does some extraordinary surgeries. He’s doing things that specialists in the U.S. would do—and he’s doing them well without having all the resources. Often we would find ourselves out of supplies and having to improvise.

Are there any patients whose stories moved you?

We had a ten-year-old child come in with tetanus. One of the important things for anybody with tetanus is to recover in an un-stimulating environment. So, there was a quiet room on one end of the male ward where this child stayed. The treatment is sedation, antibiotics, and time. This particular child was in an age category where a positive outcome was expected, as long as his therapy was maintained.

He had a couple difficult days and then he started getting better and better very quickly. He had to learn how to walk and eat again. But the day before we sent him home, he started acting like your standard ten year old, giggling and squealing and causing harmless mischief—just the pesky fifth grade kid you wanted to see him become. That’s when I knew it was time for him to go home, because he was finally able to act like a regular ten year old.

We had another little boy come in with rabies. I had got a call from somebody saying, “there’s a boy who’s acting strangely.” I went over to the exam room, and there was a child who had been bitten by a dog back in November. This was now May.

There’s no statute of limitations on rabies. They talk about people being afraid of water when they have rabies, but I had never witnessed it. I’ve seen people with rabies but never like this. It was striking. His mother would hold water up to him and he would become anxious to the point of panic. He was probably days away from death. We told his mother we’d be happy to admit him, but sadly, the only thing we could do was sedate him. His mother was so courageous and it touched me. She chose to take him home and, though I don’t know for sure, he likely only lived for another two days or so.

What do you tell people when they ask about your experience?

I think people spend way too much time worrying about me when the story really isn’t about me. It’s about the people that I served. These folks have survived so much, from war and bombings to their own pandemic—drought. Their heroism is pretty amazing and that’s what I’m trying to communicate to people when they ask me to talk about my experience.