Volunteering in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan

Dr. James (or Jim) Peck, general surgeon and volunteer, was recently back at the CMMB head quarters in New York, this time to inspire our next cohort of international volunteers. He joined fellow volunteer, Stephanie Summa, to share words of advice and answer questions about their experiences serving in low-resource settings.

Dr. Jim talked about his many mission experiences, focusing on his service at the Mother of Mercy Hospital in the Nuba Mountains of Sudan. His role there: filling in the shoes of Dr. Tom Catena.

Tell us about the Nuba Mountains and Mother of Mercy Hospital

The Nuba Mountains is very, very remote and very, very hot. I’ve heard the Bishop in Sudan describe it very well. He said, “Being in Sudan is like driving a greyhound bus through the Mojave Desert.” Sudan is a desert and it is absolutely barren.

In the entire hospital there are 200 beds and 435 patients. That means that every bed hold s more than one person. Some of the children sleep three in a bed.

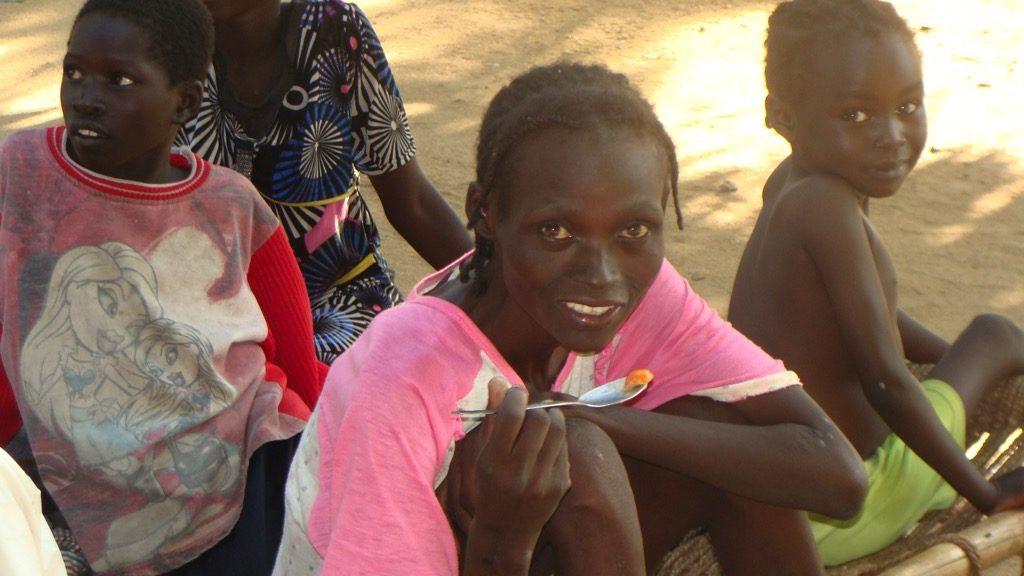

The people here live in extreme poverty. They will sell everything just to get food—their farm equipment, their animals, their clothing. Children are living in grinding poverty and suffering from severe malnutrition. Every one is very malnourished and, therefore, very anemic. Despite people not having enough to eat, they are very generous.

You will notice that many people have reddish hair. If you’ve never seen this, it’s called Marasmus and it’s common among malnourished individuals. Another common ailment in this area is malaria. The most chronic, however, is tuberculosis. The area actually has a tuberculosis and a leprosy colony.

Any words of advice?

Working in an environment like the Nuba Mountains, you are on 24 hours a day 7 days a week. I just want to impart some advice for what you need to do if you’re going to work in this kind of environment. First, just take care of yourself. This is really, really important. On one of the first missions I participated on, I was told to catch sleep whenever I could. I’ve carried this advice with me all the way to Sudan.

You have to remember that if you’re sick, the whole mission comes apart. It is so important that you take care of yourself. Another problem I encountered is that you never feel hungry because it is so darn hot. So be sure to eat.

Hydration is really important because in Nuba you sweat like crazy. There’s no air conditioning obviously, and you are working hard with few breaks. And so, you really need to take water constantly which, isn’t easy because the water isn’t bottled. But there is a deep well for the community and the water is clean. You have to make sure you keep yourself rested, fed, and hydrated.

In terms of skills, you need to be really good at conducing comprehensive physical examinations. You have to be able to use your stethoscope. I’m not fluent in the languages of the Nuba Mountains—as I imagine most of you will find depending where you are going to serve—there are multiple dialects, multiple tribal languages, and I work with an interpreter. So my physical exam becomes critically important. The only imaging advice available at Mother of Mercy Hospital is an ultrasound machine. Every place is different, but don’t expect to have all the diagnostic tools you have at hand here.

What do you think it the most important thing you bring to the field?

One of your biggest roles you will play will be your role as a teacher. Teach your staff excellent technique, it makes a huge difference. You have to be patient, kind, and very slow. Remember English is not their first language. Explain exactly what you mean and listen thoughtfully to everyone.

Dr. Tom Catena is an absolute expert at this. He listens to everyone—the nurses, the patients, anyone who needs to be heard. Another piece of advice I’ve carried with me from my very first mission is to just be flexible. You will need to handle uncertainty and as long as you are flexible you will be able to figure it out eventually.

Are there stories that stand out to you from your experience in Sudan?

I’m going to tell one of my favorite stories. I had a patient come in with no blood pressure. She was 16 years old. As a 16-year-old with no blood pressure in Nuba, you assume it’s a ruptured ectopic (when a fertilized egg implants itself outside the uterus) until proven otherwise. I remember telling the nurse anesthetist to get an IV set up. By the time I walked from where I was sleeping to where the patient was, it was confirmed to be a ruptured ectopic. We sent her to the recovery room where we left her for a few hours. After 12 hours of monitoring, she had only given out 70 CC of urine. Meaning, she was in kidney failure. I had no access hemodialysis and no idea how to handle the situation.

I knew I had to do something. I called my hospital in Portland, Oregon and asked for the doctor on call for nephrology? It was midnight my time, but I think it was mid-noon his time. Over FaceTime I asked him how to do a peritoneal dialysis? That’s where you put fluid into the abdomen and drain it out. He explained the process and what I would need.

I can’t tell you enough, you have to be flexible. Things happen all the time and you will be able to figure it out if you take a moment and think about it. You will develop the critical capacities of judgment and teamwork. You and the local staff will become a team and it is important to make sure that everyone feels a part of it. The next thing is accepting responsibility. If something bad happens or somebody dies, you have to accept the responsibility. You tried and you did your very best, but it didn’t work.

Did the 16-year-old with kidney failure make it?

Yeah, she did great. Her kidney failure was from shock, not sepsis or anything else. So I knew I just had to let her kidneys recover so she could survive. I brought her back to surgery, but I didn’t have a dialysis catheter. I just took an nasogastric tube and put it down behind her uterus. It’s just like I say, you have to take a moment to think of how you are going to treat someone because you don’t have all the resources you would want or need.

One of the most challenging things was the electricity. In Nuba, the electricity goes out six or seven times every day. Often in the middle of operating, always at the most critical moment. Without a light, you may not proceed, you may have to wait until the electricity comes back on. Almost everywhere you’ll go in the developing world you’ll be experiencing electricity problems.

Did you ever experience people or locals showing you gratitude in some way?

There are so many nice traditions that you should take advantage of. In the Nuba Mountains a meal is really a very big deal. I think one of the most important things when you first arrive anywhere new, is to make friends and to gain their trust. So just be patient with it. Hang in there.

When I first went to Sri Lanka, the head of mission said, you’re white and your American so you will get respect immediately. But it’ll last about three days and then you will have to prove yourself. Be patient with people. They will ask you to do things with them. I’ve been asked to go swimming or fishing. You will notice that family is very important. Everyone is always together, it is a big part of who they are.

You should also make sure to listen to the advice of local staff members. They’ve been there a lot longer than you have and I wouldn’t hesitate to ask how they would handle certain situations. Remember, they’ve seen surgeons from all over the world. They’ve seen different ways of doing things and they can tell you what works best for them. Don’t be too proud to ask for help.

How have these experiences changed you personally and professionally?

I think we live in Disneyland by comparison. In the US we really don’t understand what grinding poverty is. Through these experiences you learn so much about the world, so much about what’s really going on. So much so that when you come home you experience reverse culture shock. You come home, and you can’t handle everybody complaining about what seem silly things. You remember the love and the joyfulness of the people you served. They have so little but they are so joyful for what they have.

The other thing that I’ve learned has been one of the hardest things. In places impacted by war you lose patients. And the people in the Nuba Mountains are used to that. Half of the children die by the age of five. They have kids that are born and die and tragically, they have become used to it.

I remember the first time I left the operating room to speak with a father in the Nuba Mountains to say I couldn’t save his 16-year-old. His boy needed blood from a serious injury and I had no blood, I had no blood bank. He arrived too late and I couldn’t save him.

I remember telling the boy’s father that I could not save him. There was this great pause and he said “Well, man is no God.” Which is true. We are not God and we can’t do everything. You can only do your best. I think these experiences really change your view on what the world is like.